![]()

Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience

Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025 Report

INTRODUCTION

On July 21, 2025, people around the globe unite to observe Zero HIV Stigma Day, a critical moment in the ongoing struggle to dismantle the stigma, discrimination, and prejudice that continue to surround HIV. The day is more than symbolic; it is a deliberate and defiant assertion that the fight against HIV is not only a medical challenge but a social and moral imperative. Stigma in all its forms – self-imposed, institutional, and societal – remains a powerful force undermining our efforts to end the HIV epidemic. This year’s campaign theme, “HIV Stigma Warriors,” calls attention to the individuals and collectives taking bold action against all manifestations of HIV-related stigma, especially when it intersects with racism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, xenophobia, ableism, and classism.

Despite the remarkable scientific and public health progress made over the past four decades – including antiretroviral therapy (ART), the global recognition of the U=U (Undetectable equals Untransmittable) message, and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) – stigma continues to delay HIV testing, inhibit accessing PrEP, discourage ART adherence, dissuade disclosure, and drive people away from life-saving services. The 2025 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Global AIDS Update warns that stigma remains a “crucial yet under-addressed barrier” to ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. While many health indicators have improved, particularly in countries that have invested in community-led responses, progress is neither universal nor equitable. In fact, stigma continues to reinforce disparities across gender, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and geography.

In this context, intersectionality is essential to understanding the experiences of people living with HIV (PLHIV). The burdens of HIV stigma are rarely experienced in isolation. Rather, they are compounded by other forms of oppression and discrimination that shape the daily realities of individuals and communities affected by HIV. A Black transgender woman living with HIV in the southern United States, for example, may simultaneously face transphobia, racism, economic hardship, and healthcare discrimination. Each layer adds to the weight of stigma and diminishes her access to care and support. Intersectional stigma is not a theoretical construct; it is a lived reality for millions.

The urgency of confronting intersectional HIV stigma is not new, but it has taken on new dimensions in recent years. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed and exacerbated health inequities globally, demonstrating how stigma can derail public health responses and deepen social fault lines. Political and cultural backlash against LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and racial justice movements have intensified in many countries, including those that were once considered progressive in their approach to HIV. Additionally, the criminalization of key populations, including sex workers, people who use drugs, LGBTQ+ individuals, and migrants, has risen in several countries, reversing decades of advocacy and undermining HIV prevention efforts.

Meanwhile, misinformation about HIV continues to spread, especially online and in conservative media outlets. In some cases, government leaders have fueled this misinformation through moralizing rhetoric or punitive policy proposals. These developments are not merely rhetorical threats; they have tangible consequences. They embolden discrimination, deepen the shame many people with HIV feel, and weaken the public health systems tasked with providing inclusive, nonjudgmental care.

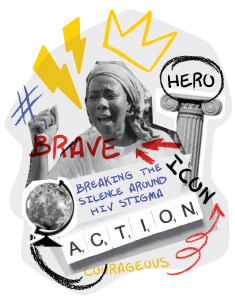

Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025 arrives at a pivotal moment. The world is five years away from the 2030 deadline to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 3.3 of ending AIDS as a public health threat. Achieving this target will be impossible without confronting the systems and narratives that continue to stigmatize PLHIV. The theme of “HIV Stigma Warriors” – a global amplification of the Stigma Warriors campaign – is an invitation to embrace the fight against stigma not as an abstract ideal but as a daily practice that must be led by PLHIV and supported by allies across sectors. Warriors in this context are not defined by violence or aggression, but by courage, resilience, empathy, and unwavering commitment to justice.

Produced as part of the global Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign, the Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience report examines HIV-related stigma in its many forms and offers a path forward. It is organized into eight sections, beginning with this introduction and followed by an executive summary and three reviews of stigma as experienced on the individual, institutional, and societal levels. These sections illuminate the scope and scale of stigma’s impact. The fifth section puts forward 25 recommendations – five each for global, regional, national, municipal, and individual actors. These recommendations reflect the diversity of responses needed to uproot stigma from the laws we enact, the systems we operate, the culture we produce, and the relationships we cultivate.

Finally, the report concludes with a call to action, underscoring the vital role that people, especially those with lived experience of stigma, must play in driving change. The HIV Stigma Warriors campaign is more than a theme; it is a movement anchored in the belief that shame and silence must be replaced with truth and action. It honors those who have stood up to stigma in the past and challenges a new generation to carry the fight forward.

At a time when populism, fear, and disinformation threaten to derail public health gains, we must redouble our efforts to create a world where no one is judged by how they live, who they love, or the virus they carry. Zero HIV Stigma Day reminds us that ending HIV stigma is not just a moral or human rights imperative; it is a precondition for ending the HIV epidemic itself. Until stigma is eliminated, no intervention, no matter how effective or well-funded, can reach its full potential.

This report is dedicated to the late Prudence Nobantu Mabele (1971-2017), in whose honor Zero HIV Stigma Day was launched in 2023, and all the HIV Stigma Warriors who refuse to remain silent – the activists, clinicians, policymakers, artists, teachers, and ordinary people who speak truth, extend compassion, and act with intention. As the core partners for the Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign, we see you, we thank you, and we stand with you. Let us work together toward a future where every person living with HIV can live free from stigma and full of dignity.

– Dr. José M. Zuniga,1,2 Florence Riako Anam,3 Sbongile Nkosi,3 Bruce Richman,4 Dr. Gary Blick5

- President/CEO, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care

- President/CEO, Fast-Track Cities Institute

- Co-Executive Director, GNP+

- Co-Executive Director, GNP+

- Founding Executive Director, Prevention Access Campaign

- Founder, Stigma Warriors Campaign

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The global fight to end HIV as a public health threat by 2030 remains one of the most ambitious and noble undertakings in modern public health history. Significant biomedical and programmatic advances – ranging from antiretroviral therapy (ART) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to campaigns such as Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U) – have transformed what was once a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition. Yet for millions of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and those most at risk of acquisition, stigma remains a pernicious and persistent barrier that compromises prevention, delays diagnosis, impedes treatment, and erodes quality of life.

Stigma – defined as the devaluation, discrimination, or exclusion of individuals or groups based on perceived difference or moral failing – is not only socially corrosive but clinically consequential. It continues to undermine public health goals, particularly when it intersects with other forms of systemic injustice such as racism, xenophobia, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, and ableism. This intersectional stigma is experienced most acutely by individuals at the margins – Black and Brown LGBTQ+ individuals, transgender women, sex workers, people who use drugs, incarcerated individuals, migrants, and others for whom societal rejection is not a possibility but a routine.

The Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience report underscores that ending the HIV epidemic requires more than access to medicine; it requires an unrelenting commitment to human dignity. This report draws on contemporary research, community insights, and cross-sectoral expertise to assess the current state of HIV-related stigma globally and to propose concrete strategies for action across multiple levels of society.

The report’s findings are sobering. While there have been incremental gains in HIV stigma awareness, actual levels of stigma and discrimination remain alarmingly high across all domains of life. Surveys continue to show that significant percentages of people, even in high-income countries with universal access to treatment, would feel uncomfortable working with, living next to, or even shaking hands with someone living with HIV. In low- and middle-income countries, where stigma is often compounded by inadequate health infrastructure and punitive legal frameworks, the barriers can be even more formidable.

Section 1 of the report explores self-stigma, defined as the internalized shame, guilt, or feelings of worthlessness experienced by people living with or vulnerable to HIV. Research reviewed in this section reveals that self-stigma remains one of the most underreported and undertreated dimensions of HIV’s psychosocial burden. Studies indicate that PLHIV who internalize stigma are less likely to disclose their status, less likely to seek or stay in care, and more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. The report draws attention to the disproportionate impact of self-stigma on women, young people, and gender-diverse populations, noting that internalized oppression is often learned early and reinforced through structural and cultural messaging.

Section 2 addresses institutional stigma, which is embedded in the policies, practices, and cultures of organizations, particularly in health, education, employment, and criminal justice systems. Health care settings – ironically, the very spaces where PLHIV seek healing – are often sites of overt and covert discrimination. The refusal of services, unnecessary use of protective equipment, breaches of confidentiality, and judgmental attitudes from providers all contribute to distrust and disengagement. Institutional stigma is further perpetuated through discriminatory laws, including the criminalization of HIV transmission or exposure, which remain in force in more than 60 countries. Such legal frameworks not only ignore the science of HIV transmission but also disincentivize testing and disclosure, thereby impeding public health goals.

Section 3 expands the lens further to examine societal stigma, which refers to the collective attitudes, beliefs, and narratives that shape public perception of HIV and those affected by it. Societal stigma is transmitted through language, media, popular culture, religious doctrine, and family systems. Although public health messaging has improved, many communities continue to frame HIV as a disease of moral failure or irresponsibility. This “othering” of PLHIV persists despite four decades of evidence proving that HIV can affect anyone and that people with an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus to others. The media’s tendency to either pathologize or sensationalize HIV, combined with limited representation of PLHIV in news, television, and film, reinforces damaging stereotypes and fosters social alienation.

Importantly, the report centers intersectionality not as a peripheral concern but as a core analytic framework. HIV-related stigma rarely exists in a vacuum. A young Black gay man in Mississippi, an undocumented Latina sex worker in Spain, a transgender woman in Kenya; all these individuals navigate layers of stigma that interact in complex ways to shape their health outcomes and life trajectories. Intersectional stigma cannot be dismantled through siloed responses. It demands holistic, multi-level interventions that honor lived experiences and recognize the compounding effects of systemic exclusion.

To that end, Section 4 provides 25 evidence-informed recommendations organized across five levels of action: global, regional, national, municipal, and individual. These recommendations range from high-level policy interventions, such as decriminalization of HIV and identity-linked behaviors, to grassroots strategies like peer-led education, stigma-free clinical environments, and local storytelling initiatives. The recommendations are anchored in existing human rights frameworks and aligned with the UNAIDS Global AIDS Strategy 2021-2026, which calls for the removal of punitive laws and policies that fuel stigma and discrimination.

At the global level, the report urges multilateral agencies and donors to not only fund stigma-reduction interventions but also hold governments accountable for human rights violations that perpetuate stigma. It also calls for the integration of intersectional stigma indicators into global HIV monitoring frameworks and the adoption of binding commitments that mirror successful models used for other global health challenges. Regional recommendations focus on context-specific strategies that reflect cultural, political, and epidemiological realities – for example, strengthening stigma-resilience networks in sub-Saharan Africa or expanding media advocacy campaigns in Latin America.

Nationally, the report recommends that governments institutionalize anti-stigma programming within national HIV strategies, reform discriminatory laws, and provide ongoing training for healthcare workers. At the municipal level, where many of the most innovative and impactful interventions are taking place across the global Fast-Track Cities network, the report highlights the need to invest in community-led responses, safe spaces, local accountability mechanisms, and intersectional service delivery. Finally, individual actions, while not sufficient on their own, are indispensable. Each person has the power to challenge prejudice, speak truth, support loved ones, and amplify stigma-free narratives.

The last section of the report is a call to action, grounded in the 2025 campaign’s theme: HIV Stigma Warriors. The theme lifts up the resilience, leadership, and creativity of people on the front lines of stigma resistance – activists, health workers, advocates, educators, artists, and everyday people who refuse to be silenced. The report calls on institutions to support these warriors, not tokenize them; to fund their work, not merely celebrate it in July; and to embed their insights into policies, systems, and cultural practices year-round.

The Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience report is both a warning and a blueprint. It warns of the consequences of complacency in the face of structural injustice, but also offers a hopeful, actionable roadmap to a world where HIV stigma no longer dictates who gets tested, who receives care, and who lives with dignity. If we fail to act boldly, stigma will continue to undermine the tremendous scientific progress we have made. But if we heed the wisdom of those most affected, and commit to change at every level of society, we can build a future where HIV stigma is a relic of the past.

SECTION 1: SELF-STIGMA AND ITS IMPACTS

Self‑stigma, often called internalized stigma, is the silent burden many PLHIV carry each day. It represents the internalization of demeaning societal attitudes and can manifest as profound shame, guilt, or fear of exposure. According to the 2023 global PLHIV Stigma Index survey, which had over 30,000 respondents across 25 countries, more than 80% percent of PLHIV reported experiencing self‑stigma at some point in their lives. That means a vast majority are battling not only a virus, but also the lingering psychological impact of stigma that persists even in the antiretroviral therapy (ART) era.

Self-stigma often begins now of diagnosis. For many individuals, learning they are HIV-positive is not just a biomedical event – it is a profoundly social and emotional rupture. Even in settings where HIV treatment is widely available, people frequently report feelings of shame, guilt, and fear of rejection. These emotions are not irrational; they are shaped by decades of stigma-enforcing narratives that equated HIV with moral failure, deviance, or promiscuity. Despite public health campaigns and community education efforts, such narratives remain embedded in cultural consciousness, particularly in contexts where sex, sexuality, and drug use are heavily policed or taboo.

A 2023 review published in Social Science & Medicine found that self-stigma remains prevalent among PLHIV across sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and North America. The review highlighted that internalized stigma was consistently associated with lower quality of life, higher rates of depressive symptoms, reduced ART adherence, and lower likelihood of achieving or maintaining viral suppression (Pantelic et al., 2023). These findings align with a 2022 WHO multi-country analysis that showed self-stigma had an independent association with delayed engagement in HIV care – even in countries with strong ART availability. The 2023 global PLHIV Stigma Index survey also revealed PLHIV who internalize negative beliefs about themselves are less likely to initiate or remain ART. In practical terms, self‑stigma erects barriers between diagnosis and care, leading to worse health outcomes and reduced viral suppression.

The psychosocial consequences of self-stigma are profound. Individuals who internalize stigma are more likely to experience chronic stress, which in turn can dysregulate immune function and accelerate comorbidities. They may avoid social relationships or sexual partnerships, fearing that disclosure will lead to abandonment or violence. In some cases, they may delay or avoid disclosing their status even to health care providers, thus perpetuating a cycle of disengagement from care. Many report censoring their speech, masking their medication routines, or relocating to avoid being recognized at HIV clinics – an exhausting reality that takes a toll on mental health and resilience.

Self-stigma does not exist in a vacuum. It is deeply shaped by the broader social context, particularly for individuals whose identities already subject them to discrimination or exclusion. For example, a 2024 study by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW) found that among women living with HIV in Kenya, self-stigma was significantly higher among those who were also survivors of intimate partner violence or who had experienced obstetric violence during childbirth. In Latin America, transgender women living with HIV reported some of the highest levels of internalized stigma – rooted not only in their HIV status but also in years of gender-based discrimination, economic marginalization, and exclusion from family and social networks (UNAIDS Latin America, 2023).

Intersectionality is therefore critical to understanding self-stigma. A young gay man in Mississippi, for example, may already navigate shame related to his sexual orientation – especially if he comes from a religious or conservative family. Upon learning he is HIV-positive, he may internalize an additional layer of stigma, reinforced by dominant cultural messages that equate being gay and HIV-positive with recklessness or moral failure. Similarly, an undocumented migrant woman in Spain who contracts HIV may feel shame not only related to her health status, but also to her perceived lack of value in a society where she is treated as expendable. These intersecting layers of stigma often compound each other, producing a sense of fatalism that undermines hope and willingness to access care.

The cost of self-stigma is not just individual – it is systemic. When people internalize stigma, they are less likely to engage with health services, leading to higher rates of advanced HIV disease, increased healthcare costs, and avoidable deaths. A modeling study published in The Lancet HIV in 2022 estimated that reducing self-stigma by even 30% could increase ART adherence rates by up to 12% globally, resulting in tens of thousands of additional individuals achieving viral suppression. The implications for public health are enormous. Self-stigma not only hampers individual well-being – it slows progress toward community viral load suppression and the broader goal of HIV epidemic control.

Importantly, self-stigma is not immutable. It can be addressed and reversed through targeted interventions – particularly those led by PLHIV themselves. Peer-led support groups have consistently been shown to reduce internalized stigma, foster self-efficacy, and improve health outcomes. One such initiative, Positive Conversations, implemented across Fast-Track Cities in southern Africa and Southeast Asia, uses storytelling and dialogue circles to help newly diagnosed individuals reframe their HIV status as a source of resilience rather than shame. Evaluations of the program show significant reductions in depression scores and improved linkage to care within six months of participation.

Similarly, Beyond Stigma’s WAKAKOSHA program, developed with young PLHIV and now being scaled in countries like Ghana, has demonstrated success in addressing self- stigma through peer-led group processes that foster emotional safety, collective healing, and agency. Early outcomes show increased confidence in navigating care systems and reduced fear of disclosure among participants. These kinds of interventions underscore the importance of investing in stigma resilience as much as viral suppression.

Education campaigns that normalize HIV as a chronic, manageable condition – and center the lived experiences of PLHIV – are also critical. For example, campaigns built around the U=U message have had a particularly powerful impact on self-stigma, especially when accompanied by visuals that depict PLHIV thriving in diverse aspects of life: parenting, careers, relationships, aging. As noted by Bruce Richman, founder of the Prevention Access Campaign, “U=U is not just a scientific fact – it’s a message of hope and dignity.” Yet as recent studies show, awareness of U=U remains limited in many parts of the world, particularly among younger generations and communities with limited access to digital health information. The U=U message needs to be talked about and promoted through education on every level – global, regional, national, municipal, and individual – to have its catalytic effect in dismantling stigma; empowering PLHIV; increasing HIV testing, ART uptake, and adherence; and transforming public perception and clinical practice to align with the science of zero sexual transmission risk when PLHIV are on ART and have an undetectable viral load.

Faith-based and cultural institutions also have a critical role to play. Where messages of shame once thrived, there is now an opportunity to foster compassion, healing, and affirmation. Progressive faith leaders across the global South have begun to speak publicly about HIV in ways that challenge stigma and uplift love, inclusion, and health as spiritual values. Programs like the “Healing the Church” initiative in Nigeria and South Africa provide theological training for pastors on HIV science, anti-stigma teaching, and inclusive pastoral care. Evaluations of these programs have shown a measurable reduction in HIV stigma, including self-stigma, among congregants.

Digital interventions are emerging as another promising approach. Mobile mental health applications tailored for PLHIV, such as Mindful Health (South Africa) and Salama+ (Kenya), offer private, stigma-free environments to access psychosocial support. These apps often combine cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) modules with peer support forums and adherence tools. While digital literacy and access remain barriers in some regions, the scalability and anonymity of these platforms make them a promising adjunct to in-person support.

Ultimately, dismantling self-stigma must be part of a broader strategy that affirms the humanity of every person living with HIV. It must include honest conversations about fear, trauma, and grief – but also joy, strength, and liberation. It must center voices that have been marginalized and embrace a narrative in which people are more than their viral load or medication adherence. And it must commit to sustained investment – not only in medical care but in the emotional and social well-being of PLHIV around the globe.

As Zero HIV Stigma Day reminds us, self-stigma is not a private weakness – it is a public issue, rooted in systemic inequity and collective neglect. To overcome it, we must act collectively, with empathy and resolve. That begins with listening to those who have lived it, believing their stories, and walking alongside them in the journey from shame to strength.

Quotes from Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign partners:

“Self-stigma is the quiet, persistent echo of messages that deem people living with HIV as unworthy or broken. It distorts identity, diminishes self-worth, and compromises health and well-being.”

– Florence Riako Anam, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

“Internalized stigma is often learned early and reinforced by structural and cultural messaging. It manifests as shame, secrecy, and fear that isolate individuals from care and community.”

– Sbongile Nkosi, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

“Self-stigma is not immutable. It can be addressed and reversed through peer-led support, community storytelling, and culturally rooted interventions like U=U that affirm the full humanity of people living with HIV.”

– Bruce Richman, Founding Executive Director, Prevention Access Campaign

SECTION 2: INSTITUTIONAL STIGMA AND ITS IMPACTS

Institutional stigma refers to the systematic policies, procedures, and practices embedded within organizations – such as health care systems, legal frameworks, education sectors, and workplaces – that disadvantage, exclude, or harm people based on their HIV status. Unlike self-stigma, which is internalized, or societal stigma, which reflects prevailing attitudes and norms, institutional stigma operates at the structural level. It manifests through discriminatory laws, biased clinical protocols, punitive criminal justice policies, and resource allocation decisions that create or reinforce unequal power dynamics. In the context of HIV, institutional stigma is not only a violation of human rights – it is a public health failure.

Around the globe in 2025, institutional stigma remains a formidable barrier to achieving equitable access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care. Despite widespread recognition of stigma as a critical impediment to health outcomes, and despite decades of advocacy from communities of PLHIV, many countries continue to enforce laws and institutional norms that punish, marginalize, or deprioritize those affected by HIV – especially when they belong to other marginalized populations.

The most visible example of institutional stigma is the criminalization of HIV exposure, non-disclosure, or transmission. As of this year, more than 60 countries continue to maintain HIV-specific criminal statutes, while others apply general criminal laws to prosecute PLHIV for acts as benign as spitting or consensual sex between partners with full awareness of one another’s status. These laws, often introduced in the early days of the HIV epidemic when little was known about transmission risks, remain largely unchanged despite scientific consensus that PLHIV who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit HIV sexually. The World Health Organization (WHO), UNAIDS, and multiple public health experts have called for the repeal of such laws, citing not only their ineffectiveness in curbing transmission but also their role in driving people away from testing and treatment. The U=U message should be central to legal reform as a legal and ethical imperative that compels institutions to update outdated laws, dismantle criminalization frameworks, and treat PLHIV with dignity, not suspicion.

A 2017 AIDS Behavior review of empirical studies on criminalization of HIV exposure in the United States found that criminalization influences public health practices and behaviors related to the HIV continuum of care. This influence is amplified among sex workers, people who use drugs, and LGBTQ+ individuals, who may already be subject to surveillance, harassment, or violence by law enforcement. In the United States, more than 30 states still have outdated or overly broad HIV criminalization laws on the books – many of which disproportionately impact Black and Brown communities, revealing the racialized application of institutional stigma.

Health care systems themselves are also common perpetrators of institutional stigma. While health providers may express compassion and commitment on an individual level, the systems within which they operate often perpetuate discrimination through outdated protocols, implicit bias, and lack of accountability. For example, studies across sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia have documented routine breaches of confidentiality, coercive testing practices, and denial of services for PLHIV – especially for women, sex workers, and transgender people. In a 2024 cross-country assessment by the International Community of Women Living with HIV (ICW), 42% of respondents in Kenya, Nigeria, and Malawi reported being denied sexual or reproductive health services after disclosing their HIV status.

In many countries, pregnant women living with HIV are subjected to institutional policies that mandate sterilization or pressure them into unnecessary cesarean deliveries, even when their viral loads are undetectable. These violations of bodily autonomy are compounded by a lack of informed consent and the absence of legal recourse. The consequences are devastating: mistrust in health systems, underutilization of maternal health services, and intergenerational trauma passed from mother to child.

Training for health workers rarely includes comprehensive education on HIV, much less the intersectional realities that shape the lives of PLHIV. As a result, health workers may exhibit discriminatory behaviors rooted in fear, misinformation, or unconscious bias. In some clinical settings, PLHIV are marked by different-colored folders, served at separate pharmacy windows, or placed at the end of appointment queues – all physical manifestations of their othering. Even in high-income countries, PLHIV report being treated differently by dentists, surgeons, and general practitioners who unnecessarily question their lifestyle in ways that imply blame. Integrating the U=U message into all health worker training is essential to counteract this stigma. By destigmatizing an HIV diagnosis and living with HIV, U=U affirms that PLHIV deserve the same standard of care, respect, and inclusion as any other patient.

Workplaces and educational institutions are not exempt from institutional stigma. In many parts of the world, PLHIV are fired, demoted, or denied employment based solely on their status. Although such actions violate international labor standards, national enforcement mechanisms are often weak or nonexistent. In the Philippines, recent reports indicate that people testing positive during pre-employment medical screenings, despite the illegality of such screenings, are quietly excluded from hiring. In South Africa, schoolchildren living with HIV have been outed by teachers or denied enrollment under the guise of “protecting other students.” These violations not only harm individuals but also send a chilling message to others who may delay testing or treatment to avoid similar consequences.

Institutional stigma is further perpetuated by the underfunding or outright exclusion of HIV-related services from broader health and development strategies. In some countries, HIV services are treated as vertical programs divorced from primary care systems, reinforcing the idea that HIV is a separate and often shameful condition. This structural siloing means that PLHIV must navigate multiple disconnected systems to access care, increasing the likelihood of disengagement. Moreover, budget cuts and shifting political priorities, especially in the wake of COVID-19 and global austerity measures, have reduced funding for stigma-reduction programs, legal aid, and community-led monitoring.

For those affected by multiple forms of institutional stigma, the consequences are compounded. A Black transgender woman living with HIV in Brazil may face police profiling, denial of gender-affirming care, and misgendering in clinics, in addition to discrimination based on her HIV status. An Indigenous man in Canada who uses drugs and lives with HIV may be denied harm reduction services or face forced detoxification. These intersectional realities require institutional responses that are not merely reactive, but structurally transformative.

Fortunately, there are emerging models of institutional reform that offer hope. In Thailand, a national accreditation system now scores hospitals on the quality of their HIV-related services and includes stigma-free certification. In Portugal, national guidelines mandate that all public-sector employers implement HIV anti-discrimination protocols, with enforcement mechanisms tied to federal funding. In Botswana, community-led health monitoring, supported by UNAIDS and local PLHIV networks, has led to the removal of discriminatory signage in clinics and the revision of intake procedures to protect privacy and dignity.

Training and sensitization programs are also proving effective. Initiatives like the Health Equity Training Academy in Fast-Track Cities across Latin America and the Caribbean are equipping municipal health departments with tools to understand and address institutional stigma. These programs use case studies, simulation exercises, and community testimonials to challenge unconscious bias and promote human rights-based approaches to care. Evaluations show increased provider knowledge and reductions in discriminatory behaviors after six months of participation.

At the legal level, growing recognition of the harms caused by HIV criminalization has led to reforms in countries such as Canada, Zimbabwe, and parts of the U.S. In 2024, the state of Illinois became the third in the United States to fully repeal its HIV criminalization law, following years of advocacy by community-based organizations and legal scholars. The reform process not only addressed the outdated legal framework but also prompted a broader societal conversation about HIV, race, and public health.

Still, these examples remain exceptions rather than the norm. For institutional stigma to be eliminated, governments and institutions must go beyond symbolic statements and implement binding policies backed by enforcement. This includes allocating sustained funding for stigma-reduction work, integrating anti-discrimination mandates into all levels of service provision, and ensuring meaningful involvement of PLHIV in governance and oversight.

Zero HIV Stigma Day challenges institutions to move from complicity to accountability. Institutional stigma is not simply the result of ignorance or malice; it is a product of decisions made, systems maintained, and harms tolerated. Reversing it will require a deliberate, sustained effort to change not only what institutions do, but how they do it, whom they serve, and whose voices are elevated in the process. It will also require an acknowledgment that stigma does not begin or end with HIV – that the same systems that stigmatize PLHIV often stigmatize Black and Brown people, queer people, poor people, and disabled people in the same breath.

Eliminating institutional stigma is possible. But it must be pursued with urgency, guided by science, grounded in human rights, and led by the very communities most impacted. Only then can our systems of care become systems of justice.

Quotes from Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign partners:

“Institutional stigma is not simply a product of ignorance – it is often a function of policy choices, entrenched biases, and unchecked power. Health systems, schools, and legal frameworks continue to deny services, dignity, and rights to people living with and affected by HIV.”

– Dr. José M. Zuniga, President/CEO, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care and the Fast-Track Cities Institute

“When patients are marked by different-colored folders or treated last at clinics, they are being systemically othered. These daily indignities erode trust and disengage people from life-saving and -enhancing HIV care. Stigma is not aligned with science or justice.”

– Dr. Gary Blick, Founder, Stigma Warriors Campaign

SECTION 3: SOCIETAL STIGMA AND ITS IMPACTS

Societal stigma is the most pervasive and culturally entrenched form of HIV-related stigma. Unlike self-stigma, which lives inside individuals, or institutional stigma, which resides in policies and systems, societal stigma is a collective phenomenon. It is produced and reinforced by norms, beliefs, language, customs, and power structures that shape how people perceive HIV and those who live with it. Societal stigma makes HIV a moral issue rather than a health condition; it codes people as “risky,” “dirty,” “promiscuous,” or “irresponsible” based solely on their diagnosis, their behavior, or their perceived association with the virus. And while public discourse may have evolved in some regions since the darkest days of the HIV epidemic, societal stigma remains remarkably resilient in 2025 – especially when compounded by racism, homophobia, transphobia, sexism, and xenophobia.

At its core, societal stigma is about social exclusion. It draws lines between the acceptable and the deviant, the innocent and the guilty, the healthy and the infected. These binaries are often fueled by media narratives, religious doctrine, educational systems, and political rhetoric that frame HIV not just as a disease, but as a symbol of moral decay. Even today, despite more than four decades of science disproving common myths, a sizable proportion of people around the globe harbor misinformed and judgmental views about HIV.

A 2024 study conducted in 15 countries revealed that 1 in 3 people would not be comfortable sharing a meal with someone living with HIV, and nearly 40% believed that people with HIV “brought it on themselves.” In the United States, a 2023 survey by GLAAD found that only 37% of Gen Z adults were knowledgeable about HIV – a figure unchanged since 2018. Alarmingly, belief in the ability of PLHIV to live long and healthy lives declined from 90% in 2020 to 85% in 2024, with the sharpest drop recorded in the Southern United States. These findings are not just statistics; they are indicators of a society that is failing to keep pace with science and justice.

Media plays an outsized role in shaping public perceptions of HIV. Television, film, and news coverage have historically depicted HIV in terms of tragedy, shame, and death. While some contemporary media have improved in their portrayals – featuring characters who are openly living with HIV, accessing care, and thriving – these representations remain rare. In many parts of the world, including conservative regions of the United States, Eastern Europe, and sub-Saharan Africa, media outlets continue to frame HIV as a punishment for immoral behavior or as a disease exclusively associated with gay men, sex workers, or drug users. These portrayals reinforce existing prejudices and dissuade individuals from seeking testing or disclosing their status.

Religious and cultural narratives are also powerful vehicles for societal stigma. In many communities, faith-based teachings associate HIV with sin, impurity, or divine punishment. These messages can be particularly damaging when they come from authority figures such as priests, pastors, and imams who are seen as moral leaders. In some cases, religious institutions have been complicit in spreading disinformation about HIV prevention and treatment, or in ostracizing individuals who are known or suspected to be living with the virus. Women living with HIV are often labeled as “immoral,” even when they contracted the virus from their husbands. LGBTQ+ individuals may face expulsion from religious communities, even when they are deeply faithful. The result is a culture of silence and fear that forces people to hide, disengage, or suffer in isolation.

Language is another conduit for societal stigma. Common expressions such as “clean” (to mean HIV-negative), “innocent” (to refer to someone without HIV), or “AIDS carrier” (a term long discarded by medical science) continue to appear in everyday conversations and public discourse. These words matter. They shape how people internalize their diagnosis and how they are perceived by others. They communicate blame, reinforce stereotypes, and embed stigma into the social fabric. Changing language is a critical but often overlooked component of combating societal stigma.

Societal stigma is rarely experienced in isolation. For people living at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities – Black men who have sex with men, transgender women, sex workers, undocumented migrants, people who use drugs – the effects of societal stigma are compounded. A trans woman living with HIV may be excluded from family, rejected by faith institutions, and harassed in public spaces – not because of her HIV status alone, but because of a society that devalues her entire identity. These layers of stigma increase vulnerability to violence, economic hardship, housing instability, and poor health outcomes. They create a hostile environment in which health-seeking behaviors are discouraged and mental health deteriorates.

Importantly, societal stigma also has measurable impacts on public health. When people fear being judged, ridiculed, or ostracized, they are less likely to get tested, disclose their status, adhere to treatment, or remain engaged in care. A 2023 meta-analysis published in The Lancet Public Health found that perceived stigma was associated with a 45% reduction in HIV testing uptake and a 30% increase in ART non-adherence. In communities where stigma is particularly intense, entire populations can remain underserved, creating pockets of high viral load and ongoing transmission. This is especially true among adolescents and young adults, who often face stigma from peers, parents, and school systems, and may be less likely to access HIV services without judgment-free environments.

The U=U message is one of the most powerful tools to disrupt societal stigma. By affirming the scientific fact that PLHIV who reach and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot transmit the virus sexually, U=U fact dismantles long-standing fears about HIV transmission, challenges the moral panic that stigmatizes PLHIV as ‘dangerous,’ and reframes what it means to live with HIV – from fear and contagion to health and connection. Yet despite its transformational potential, awareness of U=U remains low in many communities and is often absent from education, media, and faith-based discourse where it could most effectively challenge stigma.

Stigma also distorts how public resources are allocated. Politicians responding to public sentiment may deprioritize HIV funding, downplay prevention strategies like PrEP, or exclude key populations from health campaigns. In the United States, for example, political debates around abstinence-only education, transgender rights, and needle exchange programs are all influenced by societal stigma, resulting in policy decisions that ignore scientific evidence in favor of moral panic. Globally, donor fatigue and declining HIV visibility in the media have reduced the urgency once associated with the HIV epidemic, even as stigma continues to fester.

Despite these challenges, there are signs of progress. Community-based storytelling initiatives – particularly those that center the voices of PLHIV – have proven effective at reducing societal stigma. Campaigns like My Positive Story in Kenya, I’m Still Me in Jamaica, and Being Seen in the U.S. amplify personal narratives that challenge stereotypes and humanize the experience of living with HIV. Research shows that hearing a story from a person living with HIV can increase comfort levels by up to 15% (GLAAD, 2024), particularly when the storyteller shares characteristics with the audience. Representation matters not only in fiction but in real life.

Art, music, and performance also offer powerful tools for dismantling stigma. Theatre-based interventions in Zambia, photo exhibitions in Brazil, and spoken word poetry workshops in Chicago have all created space for dialogue, empathy, and cultural shift. These artistic expressions can reach audiences that traditional public health messaging may not, and they do so in ways that resonate emotionally as well as intellectually.

Social media, while a double-edged sword, has also become a space for stigma resistance. Hashtags like #UequalsU, #HIVPositiveLife, and #HIVStigmaWarriors have cultivated global communities of support and advocacy. Influencers living openly with HIV, such as Ongina (U.S.), Bisi Alimi (Nigeria/U.K.), and Phuti Lekoloane (South Africa), are using their platforms to educate, normalize, and challenge discrimination. At the same time, disinformation campaigns and trolling remain threats that must be addressed through platform accountability and digital literacy efforts.

Addressing societal stigma requires a comprehensive, cross-sectoral approach. It means integrating HIV education into school curricula, encouraging faith leaders to preach compassion over condemnation, training journalists to avoid sensationalism, and promoting positive images of PLHIV in media. It also means challenging the narratives we tell ourselves about who deserves care, who can live well, and who belongs in our communities. In short, it means reshaping culture.

On this Zero HIV Stigma Day, we are reminded that the fight against HIV is not just a medical or political battle – it is a cultural one. Societal stigma is not inevitable; it is constructed. And because it is constructed, it can be deconstructed. But doing so requires all of us: parents, teachers, journalists, politicians, artists, and ordinary citizens. We must choose to be allies, to speak up when silence might be easier, and to make room in our communities for every person, regardless of their viral load, identity, or past.

To dismantle societal stigma is to affirm the inherent dignity of PLHIV. It is to build a world in which health is not conditional on worthiness, and where love is not withheld because of fear. That world is possible. It begins with each of us.

Quotes from Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign partners:

“Societal stigma is the air we breathe – saturated with fear, judgment, and misinformation. It frames HIV not as a virus but as a moral failing, punishing people not for their choices but for who they are.”

– Sbongile Nkosi, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

“Despite decades of public health education, myths about transmission and morality remain pervasive. These narratives are reinforced by media, cultural institutions, and everyday language that dehumanize people living with and affected by HIV.”

– Bruce Richman, Founding Executive Director, Prevention Access Campaign

“Intersectional stigma magnifies the harm of societal rejection. For people living at the intersection of HIV and other marginalized identities, the consequences are often isolation, violence, and lost opportunity.”

– Florence Riako Anam, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

SECTION 4: RECOMMENDATIONS ACROSS FIVE LEVELS OF ACTION

Addressing HIV and intersectional stigma requires action across multiple layers of society. From global policymaking bodies to individual choices and behaviors, each level has a distinct and indispensable role in eradicating stigma and advancing the right to health for people living with and affected by HIV. The U=U message should be leveraged at every level as both a scientific fact and a humanizing narrative that dismantles fear, restores dignity, and reframes what it means to live with HIV. The following recommendations offer a framework for bold and coordinated action, emphasizing the importance of centering lived experience, grounding responses in human rights, and ensuring accountability across sectors.

Global Level: Shaping a Stigma-Free International Architecture

At the global level, the architecture of multilateral health governance plays a crucial role in setting norms, allocating resources, and catalyzing coordinated action. However, efforts to address stigma have historically been underfunded and inconsistently measured within global health responses. The following five recommendations are aimed at embedding stigma elimination more deeply within global strategies and institutions:

- Institutionalize anti-stigma goals within global HIV frameworks. Agencies like UNAIDS, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (Global Fund), and WHO should adopt measurable stigma-reduction goals as core performance indicators in their strategic frameworks. Stigma must no longer be treated as a peripheral social issue, but rather as a central determinant of health outcomes.

- Promote global decriminalization of HIV and associated identities and behaviors. The persistence of punitive laws related to HIV non-disclosure, same-sex behavior, sex work, and drug use continues to legitimize stigma and deter health-seeking behaviors. The UN and other multilateral actors must intensify advocacy for legal reform, including leveraging diplomatic and financial tools to incentivize change.

- Mainstream U=U as a global anti-stigma and public health tool. UNAIDS, WHO, and the Global Fund should elevate U=U within normative guidance, communication campaigns, and reporting frameworks. This includes supporting international consensus statements that affirm the science of U=U and funding global implementation to ensure all countries have the capacity to communicate the message clearly, accurately, and consistently.

- Establish a Global HIV Stigma Accountability Mechanism. A dedicated mechanism, modeled after the UPR (Universal Periodic Review) process at the UN, should regularly review national progress on stigma elimination, monitor human rights abuses linked to HIV status or identity, and provide civil society with a platform to hold governments accountable.

- Elevate stigma elimination within the 2030 SDG acceleration agenda. Global reviews of progress toward the Sustainable Development Goals must treat stigma – not just as a barrier to SDG 3 (health) – but as a transversal issue affecting SDGs related to gender equality, education, inequality, peace and justice, and reduced poverty. High-Level Political Forums and SDG summits should dedicate space to stigma metrics and solutions.

Regional Level: Contextualizing Responses in Cultural and Political Realities

Regional efforts offer the opportunity to address stigma within shared legal, linguistic, and cultural frameworks. Regional political bodies, professional associations, and advocacy coalitions can advance context-specific responses and amplify collective voice.

- Advance model anti-stigma legislation and cross-border legal harmonization. Regional bodies such as the African Union, ASEAN, the European Union, and the Organization of American States should support the development and adoption of model anti-discrimination laws that member states can adapt and implement nationally.

- Coordinate stigma-resilience networks among key populations. Regional PLHIV networks, LGBTQ+ coalitions, and sex worker unions should be supported to build capacity, share best practices (including U=U advocacy), and provide mutual support across borders. These networks play a vital role in exposing abuses, organizing resistance, and driving cultural change.

- Expand regional stigma-monitoring initiatives. Surveillance systems at the regional level should be strengthened to track stigma-related indicators (e.g., health system discrimination, criminal enforcement of HIV-related laws, media bias). Results should inform regional development strategies and policy roadmaps.

- Create regional media partnerships to challenge cultural stigma. Partnering with regional broadcasters, artists, and journalists can amplify stigma-free messaging in locally resonant formats and languages, including normalization of the U=U message as part of accurate public health narratives. Initiatives should also build the capacity of media professionals to cover HIV ethically and accurately.

- Convene regional courts and human rights institutions to address stigma-based abuse. Regional human rights courts and commissions (e.g., Inter-American Court of Human Rights, African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights) should treat stigma-based discrimination, denial of services, and criminalization as justiciable issues and offer redress to those affected.

National Level: Legislating, Funding, and Governing with Equity

National governments are responsible for the policies, legal frameworks, and public services that directly shape stigma in everyday life. They hold the power to either perpetuate or dismantle systemic barriers. These five recommendations outline actionable steps at the national level:

- Repeal laws that criminalize HIV status or associated behaviors. HIV non-disclosure, exposure, and transmission laws must be repealed or reformed to reflect scientific consensus, including the fact that PLHIV with an undetectable viral load cannot sexually transmit HIV. Simultaneously, laws that criminalize sex work, drug use, same-sex conduct, and gender non-conformity must be eliminated.

- Institutionalize stigma-free clinical training for all healthcare providers. Health worker curricula should include mandatory training on cultural humility, implicit bias, trauma-informed care, and stigma-free HIV services. National medical boards and accreditation bodies must enforce compliance.

- Enact and enforce anti-discrimination laws inclusive of HIV status. Countries should explicitly protect PLHIV from discrimination in employment, education, housing, healthcare, and social services, with strong enforcement mechanisms and legal aid access.

- Fund and scale community-led stigma reduction initiatives. Governments must invest directly in community-based organizations to design, implement, and evaluate stigma-reduction programs. This includes funding for peer support networks, storytelling initiatives, and legal empowerment services.

- Integrate U=U into national health communications and policies. National health agencies should officially endorse the U=U message, incorporate its science-based zero sexual transmission risk assertion into public campaigns, and train healthcare providers to use it as a tool of empowerment and stigma reduction.

Municipal Level: Grounding Stigma Elimination in Local Systems and Services

Cities and municipalities, especially the 550-plus that comprise the Fast-Track Cities network, are at the front lines of HIV service delivery and stigma reduction. Their proximity to communities allows for localized innovation and culturally appropriate interventions.

- Create and sustain safe, stigma-free spaces within health and community settings. Municipalities should ensure that clinics, shelters, youth centers, and social service agencies are equipped to provide stigma-free environments – including displaying U=U materials, offering clinical and service provider training on U=U, and reinforcing positive health messages through physical design, staffing, signage, and community input.

- Partner with local educators and religious leaders to foster inclusive dialogue. Local governments can coordinate with school systems and faith institutions to disseminate science-based, nonjudgmental information about HIV, challenge harmful myths, and reduce generational stigma.

- Institutionalize peer navigation and community health worker programs. Peer-led programs that embed PLHIV as service navigators, educators, and support providers have proven successful at reducing stigma. Municipalities should formally integrate and compensate these workers within local health systems.

- Launch annual “HIV Stigma Warrior” awards and campaigns. Recognizing local leaders, clinics, educators, and organizations actively working to dismantle stigma can elevate community role models and normalize advocacy efforts.

- Integrate stigma metrics in city-level monitoring and budget planning. Local governments must measure stigma and discrimination within service systems and use data to inform budgeting, staff training, and performance improvement processes.

Individual Level: Personal Accountability and Collective Transformation

While systems must change to eliminate stigma, individual choices and behaviors can reinforce or resist stigma in powerful ways. These five recommendations emphasize how individuals can function as agents of change:

- Educate yourself about HIV science and lived experience. Learn the facts: HIV is not a death sentence. U=U is real. HIV treatment works. There is zero risk of sexual transmission of HIV if you reach and maintain an undetectable viral load. Engage with personal stories of PLHIV to deepen empathy and challenge internalized biases.

- Interrupt stigma when you see or hear it. Whether in family settings, workplaces, online spaces, or casual conversation, individuals must challenge misinformation, call out derogatory language, and offer counter-narratives rooted in compassion and science.

- Share your story or amplify the stories of others. For those with lived experience, storytelling can be healing and transformative. For allies, elevating the voices of PLHIV can help create safer and more informed spaces.

- Vote and advocate for stigma-free policies. Use your voice to support candidates, ballot initiatives, and policies that protect the rights and dignity of PLHIV and other marginalized groups.

- Join or support community initiatives. From volunteering with local organizations to attending stigma-awareness events or contributing to mutual aid efforts, individuals can build solidarity and momentum within their communities.

The recommendations in the Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience report form the core of a comprehensive, multisectoral response to HIV and intersectional stigma. But implementation is key. Stigma cannot be legislated away, trained away, or funded away without a concurrent commitment to listening, learning, and acting with humility. We must build systems of solidarity as strong as the systems that once excluded, marginalized, and punished people based on their HIV status or identity. With coordinated, courageous, and community-led action, we can dismantle the machinery of stigma.

CONCLUSION AND CALL TO ACTION

CONCLUSION AND CALL TO ACTION

As we commemorate Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025, the evidence is overwhelming: stigma, in all its forms, remains one of the most powerful drivers of the HIV epidemic – and one of the least adequately addressed. Across geographies and generations, stigma continues to undermine scientific advances, sabotage public health systems, and fracture the lives of PLHIV. It manifests internally as shame, structurally as denial of care, and culturally as rejection and fear. It festers in silence, flourishes in ignorance, and feeds on policies that fail to protect the most vulnerable.

One of the most transformative tools we have in this fight is the truth behind U=U. This scientific fact affirms that PLHIV who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load cannot sexually transmit the virus. This message is much more than a biomedical tool – it is a declaration of dignity, a weapon against fear, and a message of hope. Yet, too few people know it, too few health workers communicate it, and too many systems fail to amplify it. To unmask stigma, we must also unmute U=U.

But if stigma is a learned behavior, it can be unlearned. If it is perpetuated by systems, it can be dismantled by them. If it spreads through silence, it can be undone through visibility and voice. The path forward is neither theoretical nor abstract – it is populated by people who are living proof that courage, compassion, and community can overcome even the most entrenched prejudice. These individuals are HIV Stigma Warriors, and their example lights the way. They are also the U=U advocates across continents who refuse to let outdated myths define their futures, reminding the world that U=U and that love, sex, and intimacy are not off-limits for PLHIV.

The 2025 campaign theme, HIV Stigma Warriors, is a tribute to the millions of individuals and organizations worldwide who are challenging stigma not just with words but with action. These warriors are the peer navigators in Mozambique who help newly diagnosed youth find strength in their stories. They are the transgender leaders in Argentina organizing safe spaces for care. They are the lawyers in Kenya defending the rights of HIV-positive sex workers, the clinicians in Georgia who sit eye-to-eye with patients and say, “You are not alone,” the artists in Thailand telling healing stories through music and theater. They are parents, educators, faith leaders, social workers, health professionals, and policymakers who recognize that ending stigma is not a peripheral task, but central to ending the HIV epidemic.

A warrior is not defined by their perfection or absence of fear. They are defined by their willingness to act in the face of fear, to rise even when systems tell them to shrink, and to speak even when silence is safer. Every person living with HIV who has disclosed their status to a friend, family member, or employer is a warrior. Every person who has challenged a colleague’s harmful joke, corrected a media stereotype, or voted for a pro-health candidate has joined the fight. Warriors may not always wear armor or stand on podiums, but they shape laws, shift minds, and save lives.

What the Unmasking Stigma, Mobilizing Resilience report shows us is that the fight against stigma must be fought on multiple fronts simultaneously. It cannot be the responsibility of PLHIV alone – though they remain its most powerful leaders. It must involve all levels of government, the media, academia, multilateral organizations, healthcare systems, and civil society. It must involve teachers in classrooms, policymakers in parliaments, journalists in newsrooms, and neighbors at community meetings. And it must involve individuals – each of us – examining our own prejudices, our own silences, and our own capacity to act.

This report calls for more than awareness. It calls for action that is sustained, bold, and unapologetically rooted in justice. It demands we go beyond symbolic gestures and enact real change: the repeal of discriminatory laws, the institutionalization of stigma-free clinical protocols, the funding of community-led initiatives, and the centering of intersectional realities in everything from service delivery to national health plans. It also challenges us to rethink what we mean by “health.” Health is not just the absence of disease. It is the presence of dignity. It is the freedom to live without fear of exclusion, to love and be loved, to dream and to contribute. Ending HIV stigma is not merely a means to end a virus – it is a declaration that no one should be denied their full humanity because of how they acquired a virus or who they are. That is why the fight against stigma is not only about ending HIV; it is about affirming life.

We are at a critical juncture. Just five years remain until the 2030 deadline for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including the target to end AIDS as a public health threat. If we fail to prioritize stigma now – across funding, legislation, programming, and education – we risk squandering hard-won gains and losing a generation of progress. But if we rise to meet the moment, stigma can be the thread we pull that unravels other forms of injustice. It can be the pressure point that shifts not only HIV outcomes, but gender equity, racial justice, and human rights.

The role of young people in this movement is especially vital. Gen Z is coming of age in an era where scientific truth is too often under siege, where misinformation spreads at the speed of a tweet, and where HIV knowledge is disturbingly low. Yet this same generation has shown itself to be courageous, creative, and values-driven. Young HIV Stigma Warriors, many of whom were born with HIV or diagnosed in adolescence, are using TikTok, Instagram, and art collectives to rewrite the narrative. They are rejecting shame, reclaiming joy, and refusing to let stigma define their identities. We must amplify them, fund them, and follow their lead.

Stigma is resilient, but so are we. The HIV community has always been a site of resistance and reinvention. From the earliest days of ACT UP and Treatment Action Campaign to the present-day coalitions of U=U advocates, harm reductionists, and community health workers, we have not only survived but reshaped the world. We have turned mourning into movements, pain into policy, and silence into visibility. The same resolve that brought antiretrovirals to millions, which challenged governments to act, and that turned despair into dignity must now be harnessed to defeat stigma once and for all.

As the Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025 campaign concludes, let us recommit to the work ahead. Let us honor the memory of those we have lost by protecting those still fighting. Let us build bridges across differences, show up when it is uncomfortable, and refuse to let fear make our decisions for us. Let us wear the title of HIV Stigma Warrior not as a badge of honor but as a daily responsibility. We close with this call to action:

- If you are a person living with HIV:

- Know that you are not alone, you are not broken, and you are not to blame. You are powerful. Your truth matters. Your joy matters.

- If you are a policymaker:

- Legislate with courage. Protect human rights. Fund stigma elimination like it matters – because it does.

- If you are a health worker:

- Listen with respect. Serve without judgment. Treat with compassion. Tell the truth about U=U. Let science restore dignity.

- If you are an artist, educator, or journalist:

- Tell the truth, amplify diverse voices, and use your platform to normalize – not sensationalize – HIV.

- And if you are anyone else:

- Join us. In your home, your workplace, your vote, your advocacy. We all have a role to play as HIV Stigma Warriors.

In 2025, we do not need more performative gestures. We need a groundswell of action rooted in love, accountability, and solidarity. We need HIV Stigma Warriors – everywhere. This is the charge of Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025. This is the movement. This is the moment.

Quotes from Zero HIV Stigma Day campaign partners:

“A warrior is not someone without fear; they are someone who acts despite fear and tells their truth. Every person who tells their truth challenges stigma and helps to end the HIV epidemic.”

– Florence Riako Anam, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

“Ending stigma in all its forms is not peripheral to ending the HIV epidemic – it is central. Without dismantling stigma, no scientific advance, including U=U, will reach its full potential.”

– Bruce Richman, Founding Executive Director, Prevention Access Campaign

“As Prudence Mabele reminded us, we do not need more gestures – we need justice-driven action. This is the charge of HIV Stigma Warriors and the call of Zero HIV Stigma Day 2025.”

– Sbongile Nkosi, Co-Executive Director, GNP+

“HIV stigma is resilient, but so are we. The HIV movement has always found a way to transform pain into power and turn exclusion into a commitment to care for one another.”

– Dr. José M. Zuniga, President/CEO, International Association of Providers of AIDS Care and the Fast-Track Cities Institute

“The title ‘HIV Stigma Warrior’ is not a badge; it is a daily responsibility. Being an HIV Stigma Warriors calls each of us to show up, speak out, and act with unwavering solidarity.”

– Dr. Gary Blick, Founder, Stigma Warriors Campaign