IAPAC SPECIAL REPORT

Disrupt to Deliver: Reimagining PrEP

FOREWORD: MESSAGE FROM IAPAC’S PRESIDENT/CEO

Scientific innovation has delivered unprecedented prevention tools – from oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to long-acting injectable options – but access to these tools remains grossly unequal. Fewer than one in four individuals globally who could benefit from PrEP are currently able to access this critical prevention tool. The vast majority are those systematically marginalized: young people, key populations, and communities living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), many of whom face additional legal, social, and structural barriers to care.

This sobering reality long in the making is not just a failure of policy or logistics. What we have witnessed since the advent of PrEP in 2014 is a failure of imagination, urgency, and global solidarity. We cannot end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030 using incremental approaches that simply reinforce the status quo. Tinkering around the edges will not overcome entrenched inequities or deliver justice to those left behind. We must reject the inertia of what is politically palatable in favor of what is morally imperative. What is required now is disruption – strategic, intentional, and unapologetically bold.

In this spirit, IAPAC’s Disrupt to Deliver: Reimagining PrEP special report explores the global HIV prevention ecosystem, with a particular focus on PrEP. This special report is not a checklist; it is a provocation grounded in evidence but driven by a sense of moral responsibility to challenge what we accept as normal in prevention access. And while IAPAC does not pretend to have all the answers, we are bold enough to put forward a bolder vision. A vision in which equity, dignity, and person-centered care are foundational pillars.

We also recognize that a solely rights-based approach, while essential, is not sufficient on its own to galvanize the scale and systems change required. Therefore, this special report integrates three complementary frameworks to strengthen our argument and expand our reach.

- First, we take a health systems strengthening framework – understanding that PrEP cannot succeed in isolation from the systems meant to deliver this highly effective prevention tool. This approach entails training diverse cadres of providers, integrating PrEP into routine and primary care, enabling task-shifting, improving supply chains, and embedding PrEP delivery in universal health coverage (UHC) pathways. It also means viewing PrEP uptake as a measure of how resilient, responsive, and equitable our health systems truly are.

- Second, we adopt a public health and HIV epidemic control framework. PrEP is not only a human right; it is a proven public health tool capable of dramatically reducing HIV incidence. We frame PrEP scale-up within national strategies to reach HIV epidemic control, using metrics like the PrEP-to-need ratio (PnR), infections averted, and treatment cost savings. This epidemiological framing complements our equity arguments with population-level justifications for rapid expansion, making the case that failing to scale up PrEP is not only unjust, but unsustainable.

- Third, we engage with an innovation and market shaping framework. Disrupting the prevention status quo also requires reshaping the marketplace. This means challenging monopolistic pricing, accelerating generic and biosimilar pathways, and testing new financing models such as global subscription platforms. We advocate for pricing that recognizes financial barriers to PrEP access, expanded voluntary licenses for generic manufacturing and distribution, regional manufacturing hubs for supply chain sovereignty and stability, and pooled procurement initiatives to lower prices through aggregated demand. Innovation must go beyond products and include delivery, pricing, regulatory strategies, and public-private partnerships that accelerate access and affordability.

The report maps cross-cutting and regional barriers and offers a suite of disruptive actions. From breaking pricing monopolies to imagining subscription-based access for middle-income countries, to expanding publicly owned regional manufacturing hubs – each recommendation aims to shift power toward those who are currently underserved. We also envision a reimagined HIV prevention ecosystem – one where communities lead; where integration with primary care is the norm; and where data, technology, and compassion converge to drive scale and sustainability. And we close with a call to action – not simply to act, but to transform.

IAPAC has long championed the integration of prevention and treatment within a unified HIV response. A decade before PrEP gained wide recognition as a cornerstone of HIV prevention, we helped shape the global discourse around its role as a critical adjunct to antiretroviral therapy (ART)-based treatment as prevention (TasP), now known as U=U (Undetectable = Untransmittable). At the XIX International AIDS Conference in 2012, IAPAC issued a forward-leaning consensus statement – Controlling the HIV Epidemic with Antiretrovirals: Treatment as Prevention and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis – which called for bold action to scale up both TasP and PrEP as synergistic strategies. Our consensus statement underscored the imperative to address implementation barriers, including stigma, healthcare workforce gaps, and systemic inequities, many of which persist to this day, and are included in this special report.

I am proud of this IAPAC special report and the dedication and resolve of the clinicians, researchers, public health experts, and community leaders who are striving toward a future where PrEP is accessed by millions more people around the globe. My thanks as well to Dr. Linda Gail-Bekker (Desmond Tutu HIV Foundation, South Africa) and Dr. Jonathan Mermin (in his personal capacity) for reviewing and commenting on this special report, thus helping to shape its framing. By marrying rights with resilience, public health with personhood, and equity with economic innovation, this special report seeks to move beyond silos and ideologies. IAPAC invites stakeholders across sectors and disciplines to meet this moment. We cannot retreat to what is familiar, especially as we face an unprecedented assault on the global HIV response.

I am equally humbled by what remains unknown – and by the challenges ahead. But what I know with certainty is that we cannot deliver a different outcome unless we dare to disrupt. The Disrupt to Deliver: Reimagining PrEP special report is IAPAC’s initial contribution to that disruption.

In solidarity,

Dr. José M. Zuniga

President/CEO

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION 1: A MOMENT OF CRISIS AND OPPORTUNITY

SECTION 2: DISSECTING CROSS-CUTTING BARRIERS TO PrEP SCALE-UP

SECTION 3: TAILORING PrEP SCALE-UP STRATEGIES TO REGIONAL CONTEXT

SECTION 4: DISRUPTING THE STATUS QUO WITH DISRUPTIVE ACTION

SECTION 5: REIMAGINING THE HIV PREVENTION ECOSYSTEM

SECTION 6: CLOSING THE DISTANCE BETWEEN PROMISE AND PRACTICE

SECTION 1: A MOMENT OF CRISIS AND OPPORTUNITY

Four decades into the HIV epidemic, the world finds itself in a paradox. On one hand, scientific innovation has delivered the most robust suite of prevention tools in the history of infectious disease – oral PrEP, long-acting cabotegravir (CAB-LA) and, most recently, long-acting lenacapavir (LEN-LA) for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). On the other hand, these tools remain out of reach for the vast majority of those who need them most. The global HIV prevention response, particularly as it relates to PrEP uptake and scale-up, is failing not due to a lack of science, but because of political inertia, regulatory dysfunction, systemic inequality, and a persistent underestimation of the urgency of prevention.

In 2023, 1.3 million people acquired HIV – almost three times the number needed to stay on track to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. While the global community has set ambitious targets – fewer than 370,000 new infections by 2025 and a 95% reduction in new infections by 2030 – the trajectory is far off course. UNAIDS data show that even in countries where PrEP is available, uptake is low, adherence is uneven, and persistent stigma, weak health systems, and legal and cultural barriers continue to suppress demand and access. The most at-risk communities – adolescent girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa, gay and bisexual men, transgender people, sex workers, people who inject drugs, and migrants – are often those least served by prevention programs. This is not a gap. It is a chasm, and one that we must address with the urgency it demands.

The Disrupt to Deliver: Reimagining PrEP special report centers on one core belief: that the global HIV prevention response must be radically reimagined. We must stop assuming that conventional health system logic will be sufficient. We must stop treating PrEP as an add-on and start treating it as a cornerstone of public health strategy. We must disrupt the silos, cost structures, delivery models, and regulatory paradigms that have allowed 21st century HIV prevention tools to languish in 20th century systems. The world cannot afford to remain passive in the face of HIV preventable infections and avoidable deaths.

We propose a new approach that is unapologetically disruptive, equity-driven, and grounded in community power. We call for a rethinking of HIV prevention not as a series of vertical interventions but as an integrated ecosystem in which PrEP access is as fundamental as vaccines and as universal as contraceptives. We envision a future where adolescent girls and young women can access PrEP in schools, where transgender communities co-lead PrEP delivery strategies, where oral, injectable, and on-demand PrEP are offered at mobile clinics, retail pharmacies, and community spaces without fear, shame, or delay.

This new vision must address the full continuum of barriers that stifle progress in HIV prevention. Achieving this vision requires tackling cross-cutting issues such as criminalization, healthcare provider bias, regulatory delays, out-of-pocket costs, and social stigma. It also means developing a nuanced understanding of how these barriers manifest regionally – from procurement inefficiencies in Latin America to age-of-consent laws in East Africa to cultural taboos in Southeast Asia. Scaling PrEP globally requires more than distributing pills or injections; it demands structural transformation.

Importantly, this reimagined prevention strategy is not about choosing between tools but about delivering choice itself. A truly person-centered approach means acknowledging that different modalities work for different people at various times in their lives. A young woman in Nairobi may want oral PrEP today and injectable PrEP tomorrow. A sex worker in Bangkok may need PrEP bundled with STI treatment and contraception. A gay man in São Paulo may prefer telehealth services and discreet delivery by mail. A migrant in Paris may only trust a peer-led service. We must meet people where they are – not where our systems are comfortable operating, with equity as a human rights priority.

In addition to a human rights-based imperative that centers equity, dignity, and choice, we must now operationalize three complementary approaches: health systems strengthening, public health and epidemic control, and innovation and market shaping.

- The health systems strengthening approach urges us to move beyond vertical, siloed HIV prevention efforts and instead embed PrEP delivery into broader health systems architecture. This means building resilient, person-centered service delivery models, strengthening health workforces, integrating digital and community-based care, and addressing supply chain vulnerabilities that limit access to PrEP commodities. It also underscores the critical role of primary care as a delivery platform for prevention. PrEP must not be an isolated intervention but one seamlessly interwoven into the continuum of care.

- The public health and epidemic control approaches reposition PrEP not only as a moral imperative, but also as an epidemiological necessity. The scale-up of PrEP must be guided by data on HIV incidence, transmission dynamics, and coverage gaps. Using modeling and population-level impact assessments, we must direct resources to those areas and populations where PrEP can have the greatest effect on epidemic control. Governments, donors, and program planners must be compelled by the logic of HIV prevention as a critical path to achieving SDG 3.3.

- The innovation and market shaping approach recognizes that availability without affordability or accessibility is not equity. This framework challenges us to disrupt current procurement mechanisms, intellectual property constraints, and pricing regimes that have slowed the introduction of new PrEP products. It invites governments and donors to leverage tools such as advance market commitments, pooled procurement, voluntary licenses, and technology transfers to ensure a steady, affordable supply of both established and next-generation PrEP formulations.

Taken together, these proposed approaches offer a bold and actionable complement to the human rights imperative that has rightly guided much of the HIV prevention advocacy to date. They respond not only to the needs of communities most affected by HIV, but also to the broader systems, markets, and institutions that determine whether prevention tools are scaled effectively.

The Disrupt to Deliver: Reimagining PrEP special report offers a comprehensive roadmap to get there. In the sections that follow, the report dissects cross-cutting barriers that inhibit progress, offers region-specific recommendations, and lays out a vision for a reimagined HIV prevention ecosystem grounded in rights, systems, public health logic, and market realism. Throughout, the report defines a moment that demands acting beyond incrementalism and rejects the normalization of 1.3 million preventable HIV infections per year.

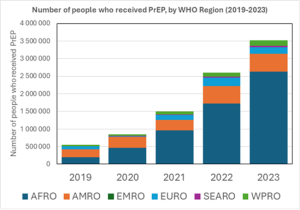

Figure 1.1 Number of People Who Received PrEP by WHO Region (2019-2023)

Source: WHO, 2025

SECTION 2: DISSECTING CROSS-CUTTING BARRIERS TO PrEP SCALE-UP

The promise of biomedical HIV prevention is not failing due to scientific inadequacy, it is faltering because of deeply entrenched, cross-cutting barriers that continue to block the full and equitable uptake of prevention tools. These barriers are not incidental. They are systemic, predictable, and in many cases intentionally maintained through political neglect, discriminatory policy, underinvestment, and attempts to make marginalized communities invisible.

Additionally, the three cross-cutting approaches outlined in the previous sections – health systems strengthening, public health and HIV epidemic control, and innovation and market shaping – must be leveraged to disrupt these barriers while supporting and amplifying community- and rights-based responses. Each of these additional approaches offers a strategic lever for dismantling the persistent constraints in policy, infrastructure, financing, and market access that have long obstructed PrEP scale-up.

This section categorizes the key cross-cutting barriers to HIV prevention and PrEP scale-up into four domains: structural and legal; health system and delivery; financial and economic; and sociocultural and behavioral. Within each domain, we describe the barrier’s scope and impact and provide five targeted, actionable recommendations designed to disrupt, not merely navigate, the systems that have failed to deliver on HIV prevention promises.

2.1 Structural and Legal Barriers to PrEP SCALE-UP

Barrier Overview:

Laws and policies that criminalize key populations, restrict access to services based on age or consent, or foster punitive environments significantly impede access to HIV prevention, particularly PrEP. According to UNAIDS, more than 90 countries criminalize some aspect of same-sex relationships, sex work, or drug use – creating an environment of fear and exclusion that drives people away from health services. Age-of-consent laws often prevent adolescents from accessing PrEP without parental approval, even as this age group is among the most at risk. Legal recognition of gender identity remains limited, further restricting access to care for trans and nonbinary people.

Consequences:

- Reduced willingness to seek PrEP due to fear of prosecution or stigma

- Inaccessibility of services for adolescents despite high incidence rates

- Disruption of funding and service delivery in legally hostile environments

- Lack of legal protections for peer navigators and community health workers

- Minimal investment in structural reforms despite clear data on their impact

Recommendations:

- Promote legislative reform to decriminalize same-sex behavior, sex work, and drug use. Link donor funding and technical assistance to legal environment improvements and support legal empowerment and protection strategies led by civil society.

- Adopt evidence-based, maturity-assessment frameworks allowing adolescents to access PrEP without parental consent. Promote model policies developed by WHO, UNICEF, and UNFPA.

- Support legislation that allows individuals to legally affirm their gender identity without medical or judicial preconditions. Facilitate access to PrEP and other health services by ensuring identity congruence in health records and insurance systems.

- Ensure funding for organizations offering legal aid, know-your-rights training, and protection services for people facing criminalization. Strengthen partnerships between health systems and legal empowerment networks.

- Mandate that structural and legal reform benchmarks are built into Global Fund concept notes, PEPFAR Country Operational Plans (COPs), and national strategic frameworks, with dedicated indicators to monitor progress.

- Recommend codifying public health non-discrimination principles into national emergency response frameworks.

- Embed legal literacy modules in health worker training to support clients navigating structural barriers.

- Prioritize legal reforms that enable public-private partnerships for PrEP service delivery.

2.2 Health System and Delivery Barriers to PrEP Scale-Up

Barrier Overview:

Even in countries where PrEP is legal and theoretically available, the health system itself often represents the greatest barrier to access. These include inadequate provider training and bias, poor infrastructure for PrEP delivery, drug and test stock-outs, restrictive laboratory requirements, and disjointed service delivery models that treat PrEP as an isolated intervention rather than part of integrated care. Provider stigma and gatekeeping remain pervasive, particularly toward transgender people, sex workers, and young people. Fragmented data systems, weak procurement mechanisms, and lack of integration with broader epidemic surveillance further compound the delivery challenge.

Consequences:

- Low provider knowledge and inconsistent counseling on PrEP options

- Inefficient service models requiring multiple visits and unnecessary tests

- Weak linkage between HIV testing and PrEP initiation

- Over-reliance on facility-based models, excluding mobile and community care

- Persistent testing and drug commodity shortages and weak procurement systems

- Failure to align PrEP with broader disease control and NCD management platforms

- Inadequate investments in digital health infrastructure for follow-up and monitoring

Recommendations:

- Incorporate PrEP-specific modules into pre-service and in-service training for doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and community health workers. Require training to address bias and structural competency.

- Allow trained nurses, community health workers, and pharmacists to initiate and manage PrEP delivery, as shown effective in multiple pilot programs. Update national policies to authorize expanded roles.

- Fund and scale peer-led PrEP services through mobile clinics, drop-in centers, shelters, pharmacies, and virtual platforms. Prioritize convenience, confidentiality, and cultural safety.

- Eliminate mandatory creatinine testing and reduce the number of clinic visits required to initiate and continue PrEP, especially for low-risk users. Introduce same-day or rapid-start PrEP protocols.

- Deliver PrEP alongside STI screening, contraception, mental health support, hormone therapy, and primary care services. Incentivize integration through provider payment mechanisms and program performance metrics.

- Strengthen supply chain management and local procurement systems using digital tools and predictive analytics.

- Develop regional PrEP data integration standards aligned with broader epidemic surveillance platforms.

- Equip health systems with robust forecasting and inventory systems to prevent stock-outs.

- Prioritize training health workers in client-centered communication and stigma reduction across all service delivery points.

- Create innovation incubators within ministries of health to pilot new delivery models that address system-level bottlenecks.

2.3 Financial and Economic Barriers to PrEP Scale-UP

Barrier Overview:

Despite increased international support, access to PrEP remains heavily dependent on donor funding, and out-of-pocket costs – both direct and indirect – continue to block equitable access. Many countries have not integrated PrEP into national health insurance schemes or essential medicine lists. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), current and future long-acting PrEP innovations are likely to remain unaffordable unless licensing, pricing, and manufacturing barriers are addressed. Global market failures, including patent monopolies and opaque pricing, have created a fragmented landscape in which only select geographies benefit from economies of scale.

Consequences:

- Disproportionate exclusion of the uninsured, youth, informal workers, and migrants

- Prohibitive costs for laboratory monitoring and follow-up services

- Financial toxicity from transport, missed work, and indirect access costs

- Limited investment in PrEP by domestic governments

- Inadequate social safety nets for people in high-risk environments

- Delayed PrEP technology introduction due to restrictive trade and patent policies

- Uneven access to procurement and manufacturing partnerships across LMIC regions

Recommendations:

- Integrate PrEP into universal health coverage (UHC) schemes and essential drug lists. Allocate domestic health budgets to fund PrEP delivery, including provider incentives and community outreach.

- Pressure manufacturers to pursue voluntary licensing agreements with the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP), enabling generic production of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP in all LMICs. Support patent-pool expansion to middle-income countries historically excluded from licensing deals.

- Support regional procurement platforms to negotiate fair pricing. Publish procurement costs across countries to increase accountability and leverage negotiating power.

- Explore social impact bonds, PrEP subscription models, and co-financing arrangements with private sector partners. Use debt swaps to fund HIV prevention infrastructure in eligible countries.

- Ensure full subsidies for PrEP, lab testing, and associated services for people below a national poverty threshold, including undocumented individuals, through policy mandates and donor-supported programs.

- Expand voluntary licenses to avoid the delays and political conflict that often surround the invocation of World Trade Organization (WTO) TRIPS flexibilities, notably compulsory licenses.

- Use South-South trade agreements and regional health pacts to enable market entry of generics and biosimilars from publicly owned regional production facilities.

- Support regional regulatory harmonization (e.g., African Medicines Agency) to accelerate approval of originator, generic, and biosimilar products.

- Transfer technology and manufacturing know-how to regional producers that can make originator, generic, and biosimilar products through regional procurement mechanisms.

- Foster donor coordination to underwrite demand guarantees and reduce risk for manufacturers entering LMIC markets.

2.4 Sociocultural and Behavioral Barriers to PrEP Scale-Up

Barrier Overview:

Internalized, interpersonal, institutional, and societal stigma remains one of the most insidious barriers to HIV prevention. Misconceptions about PrEP users (e.g., sexual behaviors, sex work), cultural and religious taboos, and a lack of community-level HIV literacy deter many from even considering PrEP. Gender inequality compounds these dynamics, reducing women’s and girls’ agency in negotiating PrEP use. Behavioral economics literature also highlights the “perception gap” between actual risk and perceived susceptibility, which is particularly acute among youth and heterosexual men.

Consequences:

- Low demand for PrEP in high-risk populations

- Limited support systems for PrEP users

- Shame-based clinical encounters and breaches of confidentiality

- Distrust in health messaging due to historical abuses

- Underinvestment in community-driven demand creation

Recommendations:

- Support culturally resonant campaigns that reframe PrEP as empowerment, choice, and dignity. Prioritize storytelling, peer engagement, and community influencers.

- Use participatory methods to co-create messaging, service environments, and digital tools that resonate with diverse users, especially young people and marginalized genders.

- Normalize PrEP by embedding it into comprehensive sexuality education, using age-appropriate, evidence-based content aligned with WHO and UNESCO guidelines.

- Fund training and employment of peer educators, PrEP ambassadors, and digital navigators to support adherence and normalize PrEP use. Link with online communities and social media.

- Design programs that recognize and address the compounded effects of racism, transphobia, xenophobia, and poverty on PrEP access and HIV vulnerability. Embed anti-discrimination frameworks in program design.

- Include anti-stigma and anti-discrimination training in medical, nursing, and pharmacy curricula.

- Develop national PrEP communication strategies aligned with behavioral insights and grounded in local epidemiology.

- Ensure health messaging platforms are co-designed with communities and subject to public accountability reviews.

- Fund digital campaigns that normalize PrEP alongside vaccines and other routine public health interventions.

- Integrate PrEP awareness and literacy into community health worker outreach for chronic disease prevention and maternal health.

2.5 Conclusion: Moving from Excuses to Action

Cross-cutting barriers to HIV prevention are not new – but our tolerance for their persistence must end. The failure to scale PrEP is not the fault of the tool, but of the systems in which it is embedded. If we are to realize the vision of a world with fewer than 370,000 new HIV infections annually by 2025, and to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030, these systemic barriers must be dismantled through coordinated, well-resourced, and community-led strategies. Rights-based approaches alone are not sufficient. We must also invest in resilient health systems, enable strategic public health governance, and reshape market forces to accelerate access to innovation for all. In the next section, we turn from global patterns to regional landscapes – analyzing how these cross-cutting barriers manifest differently across geographies, and what regionally tailored solutions are needed to scale PrEP and HIV prevention equitably, sustainably, and effectively.

Table 2.1. Barrier Categories and Corresponding Strategic Recommendations

| Category | Example | Recommendation (Summary) |

| Structural and Legal | Age-of-consent laws | Mature minor policies, decriminalization, legal aid, legal worker protections, civil society public health advocacy |

| Health Systems | Stock-outs | Task-shifting, same-day start, bundled services, inventory forecasting, digital integration, epidemic data alignment |

| Financial and Economic | Cost of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP | Voluntary licenses, pooled procurement, subscription pricing, UHC inclusion, tech transfer, donor guarantees |

| Sociocultural | PrEP stigma | Community campaigns, peer-led outreach, youth media, school education, structural stigma training |

SECTION 3: TAILORING PrEP SCALE-UP STRATEGIES TO REGIONAL CONTEXT

While HIV is a global epidemic, its prevention is deeply local. The experience of an adolescent girl in Kisumu differs vastly from that of a transgender sex worker in Bangkok or a Black gay man in Atlanta. The HIV epidemic’s drivers, the sociopolitical landscape, the structure of health systems, and the level of public investment in prevention all vary significantly by region. Thus, the success of HIV prevention and PrEP scale-up hinges on the adoption of region-specific strategies that address unique epidemiological patterns and contextual barriers.

To maximize the effectiveness of regionally tailored strategies, we must integrate three additional and essential approaches: health systems strengthening to improve service delivery infrastructure and workforce capacity; public health and epidemic control to ensure that PrEP is aligned with wider surveillance, testing, and prevention goals; and Innovation and market shaping to accelerate access to new PrEP formulations and reduce costs through regulatory streamlining, pooled procurement, and technology transfer.

This section provides a region-by-region analysis of HIV prevention and PrEP scale-up, identifying key challenges and opportunities and proposing five recommendations per region to tailor and accelerate implementation in ways that are disruptive, effective, and equitable.

3.1 Sub-Saharan Africa

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 65% of global new HIV infections. Adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) aged 15-24 account for more than 25% of new infections despite representing only 10% of the population. Oral PrEP rollout has expanded in over 35 countries, yet persistent stigma, low awareness, and limited youth-friendly services suppress uptake. Long-acting CAB-LA for PrEP is registered in only a handful of countries, and rollout is minimal. Weak health infrastructure, age-of-consent laws, and supply chain constraints compound access barriers.

Bold public health leadership will be critical to reversing stagnation and ensuring that PrEP is embedded within broader HIV epidemic control strategies, including integration with family planning, maternal health, and adolescent sexual and reproductive health services. Strengthening core health systems – especially workforce training, commodity forecasting, and digital health capacity – will determine the region’s ability to manage multiple PrEP formulations at scale. Moreover, innovation in procurement, distribution, and market shaping is essential to overcome persistent affordability and access hurdles.

Key Barriers:

- Age-of-consent laws restricting adolescent access

- Gender inequality and gender-based violence

- Limited health system reach in rural and peri-urban settings

- Low PrEP awareness among AGYW and key populations

- Delayed regulatory approvals for long-acting options

- Insufficient infrastructure investments, including last-mile logistics

- Weak integration of PrEP within national disease control strategies

- Lack of regional market incentives for generic manufacturing and distribution

Recommendations:

- Accelerate efforts across African Union countries to adopt “mature minor” consent policies for PrEP access, aligning with WHO and African Charter guidance. Pair legal reforms with national campaigns to educate health providers and policymakers about adolescent autonomy and integrate adolescent PrEP access into national HIV and public health strategies.

- Design and scale interventions like DREAMS and EMPOWER that integrate PrEP into education, economic empowerment, and violence prevention programs. Train nurses, community health workers, and peer navigators to deliver PrEP services with an emphasis on empathy, gender sensitivity, and adolescent care, as part of a broader investment in health workforce development.

- Fund mobile outreach teams, peer-led drop-in centers, and pharmacy-based PrEP delivery. Prioritize rural coverage and transport voucher schemes. Incorporate PrEP distribution into broader primary care delivery reforms to ensure continuous, community-integrated services. Utilize digital health platforms for client follow-up, appointment reminders, and tele-PrEP consultations to reduce health system burdens and improve adherence.

- Provide technical assistance to national regulatory agencies and ministries of health to streamline approval and integration of long-acting PrEP into guidelines. Collaborate with regional economic communities (e.g., ECOWAS, EAC) to establish harmonized regulatory pathways and pooled demand forecasts that signal market viability to generic manufacturers. Establish public-private partnerships that facilitate regional CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP production and equitable pricing.

- Launch national and regional social marketing campaigns tailored to AGYW, MSM, and sex workers, using trusted influencers and local languages. Integrate these campaigns into national HIV prevention and public health communication strategies to normalize PrEP as part of comprehensive HIV epidemic control. Monitor reach and behavior change through community-informed metrics and feedback loops.

3.2 Asia-Pacific

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

The Asia-Pacific region exhibits concentrated epidemics among MSM, transgender people, sex workers, and people who inject drugs. HIV prevalence in some MSM communities exceeds 20%, yet PrEP coverage is below 5% region-wide. The region includes countries with high capacity (e.g., Australia, Thailand) and others with regulatory bottlenecks (e.g., Indonesia, Philippines). Many countries rely on donor funding for PrEP programs, with limited domestic integration. Social stigma, criminalization, and limited gender recognition remain pervasive.

This diversity in health system maturity, governance, and financing demands tailored approaches. Strengthening the region’s fragmented health infrastructure, including training health workers and bolstering surveillance systems, is essential for equitable PrEP delivery. Epidemic control strategies must be recalibrated to prioritize prevention, not just treatment, especially through national HIV and UHC roadmaps. Simultaneously, market shaping innovations – including pooled procurement, expanded licensing, and regional manufacturing hubs – are critical to drive affordability and availability across LMICs in the region.

Key Barriers:

- Criminalization of key populations and lack of legal protections

- Inconsistent regulatory approval of PrEP and related commodities

- Low public awareness and persistent stigma and discrimination

- Urban-rural disparities in health infrastructure and resources

- Lack of transgender-specific and youth-friendly services

- Insufficient integration of PrEP into HIV epidemic control frameworks

- Fragmented supply chains and absence of regional pricing mechanisms

- Limited investment in HIV workforce capacity for differentiated prevention services

Recommendations:

- Invest in community-based organizations to co-lead PrEP education, delivery, and support services, particularly for transgender women and sex workers. Establish formal partnerships between health ministries and key population networks to integrate community-led prevention into national HIV control strategies, ensuring their role is institutionalized within health system frameworks. Provide certification, training, and compensation mechanisms for peer-health workers as part of a broader investment in health systems strengthening.

- Create ASEAN-led mechanisms to accelerate pooled procurement of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP and future long-acting options, especially for middle-income countries (MICs) excluded from voluntary licenses. Leverage regional economic and trade platforms to establish a tiered pricing model for long-acting PrEP options, incentivizing both originator and generic manufacturers. Embed CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP into joint regional essential medicines lists and establish regulatory harmonization mechanisms to reduce lag time for country-level approvals.

- Support cross-border advocacy coalitions to challenge criminalization and strengthen human rights protections for PrEP-eligible populations. Embed legal reform efforts into broader national public health and epidemic control agendas, ensuring that laws align with evidence-based prevention goals. Integrate legal literacy and protection services into national health systems to ensure safe and rights-affirming access to PrEP.

- Invest in mobile apps, social media campaigns, and online tele-PrEP services to reach digitally connected young people and marginalized groups. Scale health system capacity for telemedicine and integrate digital prevention platforms into national e-health strategies. Promote interoperability between digital tools for testing, counseling, and PrEP adherence support. Ensure digital equity by expanding access in rural and low-connectivity areas.

- Bundle PrEP with needle exchange, methadone maintenance, hormone therapy, and STI services in drop-in and mobile centers. Fund integration of these services within national and regional public health delivery plans, particularly in settings with high HIV incidence. Strengthen supply chains and forecasting systems to ensure consistent availability of bundled services. Introduce performance-based financing for integrated service delivery that includes HIV prevention as a measurable outcome.

3.3 Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC)

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

The LAC region is characterized by concentrated epidemics, primarily among MSM, transgender women, and sex workers. HIV incidence has stagnated or risen in several countries, including Mexico and Venezuela. Brazil leads the region in PrEP scale-up, but many other countries report low coverage, inconsistent supply chains, and little access to CAB-LA for PrEP. Additionally, most countries in the LAC region were left out of a broad royalty-free licensing agreement with six generic manufacturers to produce and sell LEN-LA for PrEP in 120 LMICs, including exportation the drug to other countries outside of the 120 authorized countries. The region also faces strong structural stigma, religious conservatism, and underfunded health systems. Regional migration and humanitarian crises (e.g., Venezuela) further complicate delivery.

Despite some progress, the LAC region suffers from health system fragmentation, particularly in the provision of public services to marginalized communities. In addition to stigma and weak political prioritization of prevention, systemic issues such as inconsistent procurement mechanisms and inadequate supply chains hinder sustained access to PrEP. A public health and epidemic control framework is urgently needed to integrate PrEP within national HIV prevention plans and broader UHC efforts. Meanwhile, innovation and market shaping interventions – including pooled procurement, regional licensing arrangements, and public-private production partnerships – could significantly reduce costs and increase the availability of PrEP formulations, including CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP.

Key Barriers:

- High stigma, especially in conservative religious settings

- Poor procurement planning and inconsistent PrEP availability

- Lack of youth-friendly and gender-affirming health services

- Weak community engagement in planning and delivery

- Limited investment in PrEP by national governments

- Disjointed integration of PrEP into public health and UHC frameworks

- Inadequate support for local manufacturing or regional pooled procurement

- Gaps in workforce capacity across primary care and community health sectors

Recommendations:

- Develop a Latin American licensing and procurement initiative modeled on PAHO’s Strategic Fund, with pooled purchasing of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP, preferably generics through licensing agreements. This mechanism should be anchored in regional trade and health agreements and include incentives for both originator companies and generic manufacturers. Regional collaboration on dossier sharing and regulatory harmonization can accelerate access to long-acting prevention tools. Consider leveraging Mercosur or CELAC for cross-country joint negotiation of pricing and supply terms.

- Advocate for integration of PrEP into public insurance packages and essential medicine lists in all countries, starting with Brazil, Chile, and Colombia. Ensure PrEP is framed not as a vertical intervention but as a core preventive service aligned with national HIV epidemic control strategies. Use health systems strengthening funds to bolster service delivery platforms, improve stock management, and train primary care providers in PrEP counseling and initiation. Establish routine performance monitoring for PrEP coverage and equity within UHC accountability frameworks.

- Support transgender-led clinics and mobile services that integrate PrEP with hormone therapy, mental health, and legal support. Fund sustainable integration of these services into primary healthcare infrastructure. Offer public subsidies and licensing support to community-based providers that deliver prevention services. Establish credentialing and continuing education pathways to integrate transgender and peer health workers into formal health system structures.

- Develop youth-targeted campaigns and curriculum integration to normalize PrEP and combat stigma before sexual debut. Collaborate with ministries of health and education to integrate comprehensive sexual health and HIV prevention education that includes PrEP in national standards. Pilot cross-sectoral school-based health programs that offer on-site PrEP referral, STI screening, and mental health support. Scale up through public health system coordination with education authorities.

- Include regional migrants and refugees in national PrEP programs, with continuity-of-care mechanisms across borders. Adopt public health emergency and humanitarian protocols to ensure migrants can access free or subsidized PrEP without legal or residency status requirements. Integrate PrEP into regional humanitarian response plans and establish interoperable electronic health records between countries to support continuity of care. Invest in mobile units and digital platforms to reach migrants in border zones and informal settlements.

3.4 Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA)

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

HIV incidence and AIDS-related deaths are increasing in the EECA region. The HIV epidemic is fueled by injection drug use, punitive laws, and health system fragmentation. PrEP is available in only a handful of countries and exclusively through donor-funded pilot programs. Stigma, criminalization, and lack of political will severely hamper prevention efforts. Russia, Ukraine, and Central Asia face overlapping crises from conflict, economic instability, and state-led repression of civil society.

The underfunded and segmented nature of the EECA region’s health systems, coupled with authoritarian governance in several countries, impedes effective public health responses. Epidemic control is often deprioritized in favor of politically driven narratives, undermining HIV prevention efforts. Market shaping opportunities have not been pursued at scale, leaving the region reliant on expensive imports and donor-led procurement. There is an urgent need for regional collaboration on regulatory harmonization, pooled procurement, and the transfer of manufacturing capacity for generic and long-acting PrEP products.

Key Barriers:

- Criminalization of drug use, sex work, and same-sex relationships

- Limited or no PrEP policies and absence of political support

- Weak community health infrastructure and limited civil society space

- Regulatory restrictions on harm reduction and NGO-led care

- Rising nationalism and suppression of evidence-based health policy

- Reliance on vertical donor funding with limited domestic investment

- Lack of mechanisms for supply chain resilience and commodity production

- Disintegrated services across infectious disease, substance use, and mental health

Recommendations:

- Support coalitions advocating for decriminalization and scale-up of syringe exchange, opioid substitution therapy, and integrated PrEP services. Embed harm reduction as a central pillar of public health and epidemic control strategies. Strengthen national HIV prevention programs by institutionalizing evidence-based harm reduction approaches within ministries of health. Train public health professionals on harm reduction implementation and evaluation, and establish quality standards for service delivery.

- Fund trusted community-led NGOs to deliver services, monitor PrEP access, and advocate for policy reform, even in repressive environments. Incorporate civil society partners into formal health systems planning and national HIV prevention frameworks. Use health systems strengthening funds to build sustainable administrative and operational capacity within grassroots organizations. Protect civic space by supporting legal defense and safety mechanisms for civil society actors facing persecution.

- Facilitate PrEP access through regional hubs (e.g., Georgia, Moldova) to serve hard-to-reach countries like Belarus, Tajikistan, and Russia. Develop a region-specific procurement and distribution framework under the leadership of subregional organizations such as the Eurasian Economic Union or the CIS. Utilize pooled procurement to reduce unit costs of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP. Negotiate with patent holders for voluntary licenses that allow access in MICs currently excluded from global access agreements.

- Ensure that conflict-affected populations in Ukraine and surrounding regions have continued access to PrEP, testing, and HIV care through mobile units and cross-border services. Coordinate with global health security and humanitarian actors to include PrEP in emergency response packages. Train health professionals in humanitarian settings to administer PrEP and manage stock. Create electronic systems that allow displaced people to retain access to services across borders. Build flexible regional PrEP supply chains that can adapt during crises.

- Support regulatory fast-tracking and prequalification in countries lacking national capacity or facing political obstruction. Support a regional regulatory harmonization agenda aligned with the Eurasian Economic Commission’s technical regulatory framework. Provide technical assistance to regulatory authorities and invest in regional quality assurance labs to facilitate accelerated review and approval of both originator and generic products. Collaborate with WHO to include CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP on regional essential medicines lists and drive down prices through advance purchase commitments.

3.5 Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

The MENA region remains one of the least resourced and least visible regions in the global HIV response. HIV epidemics are highly concentrated among MSM, sex workers, and migrants. PrEP access is nonexistent outside of pilot programs in Morocco and Lebanon. Criminalization, religious conservatism, gender inequity, and conflict-driven displacement further suppress demand and hinder delivery. Surveillance systems are weak, and political commitment to HIV prevention is minimal.

Health systems in the region are often underfunded and fragmented, particularly in conflict-affected countries such as Yemen, Syria, and Libya. A lack of robust primary care systems and referral networks hampers HIV prevention service delivery. Epidemic control efforts are challenged by a dearth of population-level data, political denialism, and public health infrastructure weakened by protracted instability. Moreover, innovation in service delivery and market shaping for PrEP technologies remains negligible, with most countries lacking regulatory frameworks, pricing strategies, or domestic manufacturing capacity for prevention tools.

Key Barriers:

- Widespread criminalization and legal invisibility of key populations

- Religious taboos surrounding sexuality and HIV

- Weak data systems and underreporting of new infections

- Limited availability of community-based organizations

- Inaccessibility of PrEP for migrants and displaced people

- Fragile health systems and weak epidemic control surveillance

- Lack of regional regulatory harmonization or procurement models

Recommendations:

- Fund low-profile, confidential services in trusted spaces such as private clinics, pharmacies, and digital platforms. Integrate these services into primary healthcare platforms to reduce stigma and ensure continuity of care.

- Engage progressive faith-based organizations and religious scholars to reshape narratives around HIV prevention, PrEP, and harm reduction. Train community religious leaders as public health allies to support epidemic control through trust-building and values-based messaging.

- Support investments in integrated bio-behavioral surveillance and modeling to estimate prevention needs and demonstrate unmet demand. Develop national PrEP dashboards to support epidemic tracking and policy planning aligned with regional benchmarks.

Leverage WHO’s Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) to establish minimum public health surveillance standards for PrEP coverage and use. - Work with diaspora organizations in Europe and North America to support PrEP continuity for refugees, migrants, and asylum seekers. Link diaspora-led services to regional networks for health system strengthening, including training and knowledge exchange platforms.

- Ensure that UNHCR, IOM, and other humanitarian actors incorporate PrEP into essential health service packages in camps and host countries.

- Advocate for inclusion of CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP, as well as future PrEP formulations, in global humanitarian formularies, supported by regional pooled procurement initiatives.

- Pilot innovative delivery mechanisms, such as health e-vouchers or mobile PrEP units, to reach individuals in high-insecurity zones.

- Support regulatory harmonization across the MENA region to expedite PrEP approvals, including lenacapavir and future long-acting technologies.

- Facilitate South-South cooperation with countries such as Egypt, Tunisia, and Jordan to manufacture and supply generic PrEP through public sector pharmaceutical companies.

- Use trade mechanisms like the Greater Arab Free Trade Area (GAFTA) to create a regional market for prevention products with favorable pricing.

3.6 Western and Central Europe and North America

Epidemiological and Programmatic Context:

Though incidence is lower than other regions, high-income settings in Western and Central Europe and North America face glaring inequities in PrEP access. Uptake is disproportionately low among Black, Latino, migrant, and transgender populations. Structural racism, healthcare fragmentation, medical mistrust, and prohibitive costs for the uninsured remain significant barriers. CAB-LA for PrEP is approved but underutilized. The approval, introduction, and scale-up of LEN-LA for PrEP in the United States is a critical test case, as PrEP coverage remains far below targets, and upcoming policy shifts and budget cuts threaten access.

Despite high-resource environments, both regions display persistent structural gaps in health system capacity to deliver equitable prevention. Public health infrastructure is highly decentralized, particularly in the United States, leading to inconsistent PrEP availability. HIV epidemic control is weakened by politicization, fragmented reporting systems, and disinvestment in prevention. Innovation in market shaping is also stalled: although CAB-LA for PrEP is approved, pricing, availability, and prescribing guidelines remain misaligned with equity and access objectives.

Key Barriers:

- Racial and economic inequities in PrEP uptake

- Provider bias and inadequate cultural competence

- Fragmented healthcare systems and high out-of-pocket costs

- Limited PrEP services in rural and conservative regions

- Policy threats to coverage and access (i.e., Medicaid cuts)

- Overreliance on specialist care with minimal primary care integration

- Insufficient pricing transparency and weak incentives for generic PrEP

Recommendations:

- Incorporate peer navigators into public health systems as formal workforce members to strengthen retention and linkage to prevention.

- Mandate national and subnational coverage policies that include all PrEP formulations, including CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP, with no prior authorization or cost-sharing.

- Authorize and reimburse PrEP prescribing by pharmacists and expand access through school clinics, mobile vans, and street medicine programs.

- Mandate public reporting on PrEP uptake by race, gender identity, and geography to ensure accountability and course correction.

- Invest in coordinated public messaging that promotes sexual health, destigmatizes PrEP, and reflects the diversity of real-world users.

- Promote voluntary licensing and generic manufacturing of PrEP across European Union and North American markets to reduce costs.

- Encourage centralized purchasing and price negotiations through regional mechanisms such as the EU Joint Procurement Agreement or Medicaid Drug Rebate Program in the United States.

3.7. Conclusion: Bridging Global Ambition and Local Action

Each region has unique strengths and challenges, but all share a common imperative: to deliver HIV prevention in ways that center equity, autonomy, and access. PrEP’s potential will remain unrealized unless global stakeholders recognize the critical need for regional tailoring, and unless governments are willing to invest in regionally differentiated strategies rooted in community realities. Moreover, the success of these regional strategies will depend on deliberate investments in health systems strengthening. This includes building and maintaining human resource capacity, reinforcing procurement and supply chain systems, and ensuring that community and primary care platforms can support an expanding array of prevention technologies. The next section will outline disruptive, even unprecedented, actions that transcend the current limits of health systems and policy, moving us toward a truly reimagined global HIV prevention ecosystem.

Table 3.1 Tailored Regional Recommendations Snapshot

| Region | Key Barriers | Recommendations |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Youth access, weak systems | Age law reform, CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP rollout, youth services, decentralized delivery models, regulatory fast-tracking, community-led demand generation |

| Asia-Pacific | Criminalization, stigma | Community-led models, ASEAN pooled licensing, integration with harm reduction and gender-affirming care, legal reform, digital public health infrastructure |

| Latin America | Trans exclusion, low coverage | Regional procurement, integration into UHC, school-based education, cross-border PrEP continuity, investment in trans-led service innovation |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | Political repression, drug laws | Regional supply corridors, harm reduction, NGO empowerment, humanitarian PrEP access, health system resilience planning for emergencies and conflict |

| Middle East and North Africa | Data void, criminalization | Confidential access points, religious engagement, diaspora-based delivery models, PrEP integration in humanitarian systems, investment in surveillance capacity |

| Western and Central Europe and North America | Racial disparities, cost | Tele-PrEP, community pharmacies, scorecards, national coverage mandates, price negotiation for CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP, innovation accelerators for new delivery platforms |

SECTION 4: DISRUPTING THE STATUS QUO WITH DISRUPTIVE ACTION

Despite biomedical breakthroughs and a growing understanding of how to reach the populations most affected by HIV, the global prevention response remains too slow, too fragmented, and too inequitable. This failure is not due to a lack of tools or strategies; it stems from the limitations of a risk-averse global health architecture that favors incremental progress over systemic transformation. As a result, the gap between potential and impact continues to widen, especially in PrEP rollout.

To close that gap, we must move beyond reform. We must embrace disruption. This section proposes a set of bold, sometimes disruptive actions that challenge conventional assumptions and structures across financing, policy, service delivery, regulatory pathways, manufacturing, education, and community leadership. These actions aim not just to scale up existing tools but to rewire the systems that determine who gets access, when, and how. Taken together, they represent a call to action for those willing to redesign – not just tweak – the global HIV prevention response.

4.1 Reframing PrEP as a Global Public Good, Not Just a Public Health Imperative

PrEP remains trapped in the logic of commodification – priced, regulated, and distributed as a market good rather than a public health imperative. To unlock its full potential, we must reposition PrEP, especially long-acting formulations, as a global public good.

Disruptive Action: Establish an international framework, akin to COVAX or the Pandemic Accord, to defines PrEP as a Global Public Good and mandates access to a core package of prevention services – including PrEP – for all people at risk of HIV, regardless of geography or income.

Supporting Actions:

- Leverage the World Health Assembly and UNAIDS PCB to adopt resolutions declaring PrEP a public good.

- Establish treaty-aligned targets that obligate nations to provide access under international law.

- Link public good designation to fast-track regulatory pathways and pooled funding mechanisms.

The proposed shift would codify global responsibility for prevention access and pave the way for shared investment in delivery systems, manufacturing, and community implementation. It would also establish a foundation for a unified global health architecture in which HIV epidemic control and health equity are non-negotiable priorities.

4.2 Creating a Global PrEP Delivery Fund to Pool Resources for PrEP Scale-Up

Current funding for PrEP is fragmented, unpredictable, and donor-dependent. Donors support commodity procurement in some countries but not systems, staff, or demand generation. Domestic health budgets rarely prioritize PrEP. The result is a delivery landscape of stalled pilots and under-resourced programs.

Disruptive Action: Establish a dedicated, multilateral Global PrEP Delivery Fund (GPDF) – a catalytic financing mechanism modeled on the Global Fund but streamlined and HIV prevention-specific – to pool resources and rapidly expand access to PrEP.

Core Features:

- Focus on scale-up of both oral and long-acting PrEP in high-incidence regions.

- Fund integrated service delivery models, including peer educators, telehealth platforms, and bundled care.

- Provide matching grants to incentivize domestic co-financing and integration into UHC schemes.

- Governed by a diverse board with majority representation from community and key population groups.

The proposed GPDF would consolidate fragmented donor financing, catalyze domestic investment, and build the infrastructure necessary to deliver PrEP at scale – especially in regions left behind by current funding models. The GPDF could also function as a health systems accelerator, strengthening national infrastructure across supply chains, data systems, and human resources in alignment with broader HIV epidemic control goals.

4.3 Leveraging Regional Manufacturing and Licensing Hubs for Long-Acting PrEP

PrEP delivery is currently constrained by monopolistic pricing, patent protectionism, and limited manufacturing capacity. CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP are controlled by originator companies and, in both cases, available only through limited pathways in most LMICs.

Disruptive Action: Launch a network of regional manufacturing and licensing hubs for long-acting PrEP, coordinated by WHO, the MPP, and regional economic blocs (e.g., African Union, ASEAN, MERCOSUR).

Supporting Actions:

- Expand voluntary licenses to avoid the delays and political conflict that often surround the invocation of WTO TRIPS flexibilities, notably compulsory licenses.

- Use South-South trade agreements and regional health pacts to enable market entry of generics and biosimilars from publicly owned regional production facilities.

- Support regional regulatory harmonization (e.g., African Medicines Agency) to accelerate approval of innovator/branded, generic, and biosimilar products.

- Transfer technology and manufacturing know-how to regional producers that can make innovator/branded, generic, and biosimilar products through regional procurement mechanisms.

The proposed approach would decentralize control over PrEP production, reduce prices through competition, and shorten supply chains – critical for both health sovereignty and equitable access. It would also stimulate regional innovation ecosystems and contribute to market shaping for emerging HIV technologies.

4.4 A Global PrEP Subscription Model for Middle-Income Countries

MICs are home to 75% of people living with HIV, yet they are often excluded from licensing agreements and donor procurement mechanisms. As a result, these countries face prohibitive costs and uncertain supply. A novel model is needed to bridge the affordability gap.

Disruptive Action: Implement a subscription-based global purchasing model for long-acting PrEP drugs, currently CAB-LA and LEN-LA for PrEP, enabling MICs to pay a predictable annual fee for unlimited access.

Core Features:

- Similar to the Netflix model for hepatitis C in Australia.

- Price based on population size and estimated need, not per-dose costs.

- Incentivizes broad uptake without penalizing countries for success.

- Can be administered through the Global Fund, UNITAID, or a new GPDF.

The proposed model reduces procurement risk, facilitates budget planning, and ensures that pricing does not restrict demand generation or innovation in delivery models. It would also drive investment in forecasting and demand planning, enabling more responsive supply systems and lowering overall costs through pooled purchasing. However, the model should also integrate legal safeguards ensuring that countries retain the right to invoke TRIPS flexibilities in case of pricing abuses or supply disruptions.

4.5 National PrEP Acceleration Strategies (NPAS)

Many national HIV programs continue to treat PrEP as a niche intervention, with no national targets, timelines, or dedicated delivery infrastructure. This is a policy failure – not a resource failure.

Disruptive Action: Encourage every country with an HIV incidence >0.2% to adopt a National PrEP Acceleration Strategy with clear objectives, measurable targets, and multisectoral governance.

Key Components:

- Integration into national strategic plans and UHC benefits packages.

- Budget lines for PrEP commodities, human resources, and M&E.

- Partnership mandates with community and key population networks.

- Performance-based incentives for health facilities and providers.

NPAS would operationalize political will, accelerate scale-up, and align domestic action with global prevention goals. These strategies should also be aligned with national public health emergency preparedness plans, ensuring that PrEP delivery is protected and adapted in times of disruption.

4.6 Making PrEP Available Wherever People Live Their Lives

Facility-based delivery of PrEP is insufficient. Many at-risk individuals never enter traditional healthcare settings due to stigma, cost, or logistics. A person-centered prevention strategy must meet people where they are.

Disruptive Action: Reengineer the PrEP delivery landscape through radical decentralization, bringing HIV prevention to homes, schools, workplaces, clubs, shelters, and online platforms.

Innovative Delivery Channels:

- Community Pharmacies: Train community pharmacists to initiate and refill PrEP without physician oversight.

- School Health Clinics: Offer PrEP as part of adolescent health services, especially for AGYW.

- Virtual Clinics: Provide same-day tele-PrEP initiation with home delivery in urban areas.

- Mobile Units and Street Medicine: Deliver bundled PrEP and other prevention and harm reduction packages to unhoused and transient populations.

- Drop-In Centers: Integrate PrEP with mental health, gender-affirming care, and harm reduction services.

The proposed level of decentralization will require regulatory reform, task-shifting, and new payment models – but it is necessary to close the PrEP access gap. Moreover, such decentralization should be embedded into health systems strengthening frameworks to ensure long-term integration and scalability.

4.7 Unleashing the Power of Communities and Peer Networks

Community-led organizations remain underutilized in HIV prevention delivery, notably PrEP. They are often asked to generate demand but are rarely given control over budgets, staffing, or implementation. This is not just inequitable; it is inefficient.

Disruptive Action: Shift 30%-50% of PrEP delivery and demand-generation funding to community- and key population-led organizations through direct financing mechanisms.

Supporting Actions:

- Re-granting platforms to provide direct-to-community financing.

- Peer educator certification and workforce development programs.

- National health workforce strategies that recognize peers as essential personnel.

- Governance reform requiring community representation in national HIV bodies.

Community-led scale-up of PrEP is faster, more culturally competent, and more trusted. Yet, without shifting power and resources, community leadership will remain symbolic rather than structural. This approach also supports the creation of sustainable, decentralized public health ecosystems where communities are co-producers of health outcomes.

4.8 Promoting Accountability with a Global PrEP Data Platform

HIV Prevention efforts are undermined by a lack of real-time, disaggregated, and user-driven data on PrEP uptake, adherence, and service quality. Donors and governments rely on top-down monitoring systems that are slow, opaque, and exclusionary.

Disruptive Action: Create a Global PrEP Data Platform to function as a publicly accessible, rights-based platform aggregating real-time PrEP indicators from national programs, implementing partners, and community monitors.

Design Features:

- Disaggregation by age, gender identity, key population, and geography.

- Community-led data collection and validation components.

- Data sharing agreements built on open-source, interoperable systems.

- Dashboards that visualize progress toward equity benchmarks and 95-95 prevention targets.

The proposed platform would enhance accountability, facilitate adaptive programming, and empower communities to hold governments and donors to their commitments. It would also strengthen epidemic intelligence and support early detection of service disruptions, inequities, and coverage gaps.

4.9 Aligning Global Health Governance with PrEP Scale-Up

Global health architecture remains poorly aligned with the needs of HIV prevention. WHO guidelines are slow to update. Donors often act in silos. Regulatory agencies are uncoordinated. And international targets are inconsistently enforced.

Disruptive Action: Establish a Global PrEP Task Force, mandated by the UNAIDS Programme Coordinating Board (PCB), to coordinate and accelerate PrEP-related action across all multilateral agencies.

Mandate and Outputs:

- Set global PrEP access benchmarks (e.g., 20 million users by 2030).

- Coordinate procurement across agencies (Global Fund, UNITAID, PEPFAR, GAVI).

- Accelerate WHO guideline updates and EUL processes.

- Convene annual PrEP accountability forums with civil society majority.

The proposed task force would address the fragmentation and inertia that continue to plague global PrEP efforts and ensure cross-sectoral collaboration. The task force should also integrate a cross-cutting innovation agenda focused on horizon scanning, digital health, and AI-supported prevention tools.

4.10 Reimagining Prevention for the Next Generation

Young people under age 25 account for more than one-third of all new HIV infections globally yet remain underserved and systematically excluded from program design. Traditional models of prevention do not resonate with their lived realities.

Disruptive Action: Establish a Global Youth Prevention Corps as a cross-sector initiative to train, fund, and empower youth leaders to deliver, innovate, and evaluate PrEP and broader prevention services in their communities.

Core Components:

- Fellowships for youth-led implementation research and service delivery.

- Youth-designed prevention campaigns and content creation labs.

- Direct investment in youth-led CBOs through multilateral and bilateral funding.

- Digital hubs for sharing innovation and peer mentorship.

Reimagining HIV prevention through the eyes of young people is not optional; it is the only way to ensure relevance, reach, and results over the next decade. Incorporating youth as co-creators in epidemic control and systems design will unlock new innovations and fuel the next generation of global health leadership.

4.11 Conclusion: Disruption with Purpose, Scale, and Equity

These disruptive actions are not modest. They are ambitious, structural, and, in many cases, unprecedented. But such disruption is necessary and long overdue. If we are to reverse the trajectory of HIV transmission, especially among the most vulnerable, we must stop adapting to broken systems and start building the ones we need. A status quo rooted in inequality, delay, and fragmentation will never deliver the transformative results required to meet 2030 goals. These bold proposals offer a different path that centers the agency of communities, reclaims the moral urgency of prevention, and deploys every tool of innovation to save lives.

The proposals also move beyond short-term fixes to lay the foundation for long-term resilience. By investing in health systems strengthening, these actions bolster human resources, data infrastructure, regulatory capacity, and service integration – all of which are essential for sustained prevention outcomes. Through a public health and epidemic control lens, the proposals prioritize population-level impact, accountability, and rapid response mechanisms. And by driving innovation and market shaping, they challenge traditional pricing models, stimulate product diversification, and unlock new service delivery pathways.

This is disruption not for disruption’s sake, but for impact created by bold action anchored in purpose, driven by scale, and committed to equity. In the next section, we envision what a fully reimagined HIV prevention ecosystem could look like when these bold actions are integrated into a cohesive, equity-centered framework.

Table 4.1 Overview of Core Problems and Proposed Disruptive Actions

| Disruptive Action | Core Problem | Mechanism | Expected Impact |

| Global PrEP Delivery Fund | Fragmented and donor-dependent financing | Pooled, catalytic funding with co-financing incentives | Sustained, equitable scale-up of PrEP services; system-wide health investments |

| Regional Manufacturing and Licensing Hubs | Unaffordable prices, IP restrictions, fragile supply chains | Local production through voluntary licenses and tech transfer | Reduced cost, supply security, regional health sovereignty |

| Subscription Model for MICs | Pricing barriers, donor exclusion | Annual flat-rate access based on population and need | Predictable budgeting, expanded access, market shaping |

| National PrEP Acceleration Strategies (NPAS) | Policy neglect, weak integration | Mandated national targets, financing, and multisectoral governance | Institutionalization of PrEP within health systems; epidemic control acceleration |

| Decentralized Delivery Models | Facility-based bottlenecks, stigma, and low reach | Pharmacies, mobile units, schools, street medicine, telehealth | Increased update among hard-to-reach populations; service innovation |

| Community and Peer-Led Scale-Up | Underfunded community infrastructure, lack of trust | Direct financing and workforce integration of peer networks | Trusted delivery, cultural competence, health system diversification |

| Global PrEP Data Platform | Lack of disaggregated, actionable data | Real-time, community-validated open dashboard | Transparency, equity monitoring, adaptive programming |

| Global PrEP Public Good Framework | Commodification and inequitable access | International declaration and treaty-aligned commitments | Shared global responsibility; policy and procurement alignment |

| Global Youth Prevention Corps | Youth exclusion, low engagement | Youth-led implementation and digital innovation hubs | Increased youth uptake, future-proofed prevention ecosystem |

| Global PrEP Task Force | Siloed governance, lack of accountability | UNAIDS PCB-mandated multilateral coordination body | Governance alignment, strategic coherence, accelerated scale-up |

SECTION 5: REIMAGINING THE HIV PREVENTION ECOSYSTEM

The current HIV prevention architecture, though built with good intentions, is fundamentally unfit for purpose. It is fragmented across sectors, inequitable in access, slow to evolve, and dependent on outdated delivery paradigms that no longer align with the realities of the communities it is meant to serve. It is reactive, rather than proactive; siloed, rather than integrated; and system-centered, rather than person-centered.

If we are to fulfill the promise of biomedical prevention and halt the tide of preventable infections, we must do more than scale existing programs. We must rebuild the entire HIV prevention ecosystem. This section envisions what that reimagined ecosystem could look like across seven interconnected dimensions: governance, financing, delivery, data, workforce, integration, and community power. Each dimension includes a set of principles, structures, and innovations designed to replace stagnation with dynamism, fragmentation with cohesion, and inequity with justice. This is not an aspirational exercise; it is an operational roadmap for how to build a world in which every person, everywhere, has the tools, support, and agency to prevent HIV acquisition on their own terms.

And at its core, this roadmap integrates structural investments in health systems, embraces public health logics of population-wide reach and accountability, and leverages innovation to shape markets, reduce prices, and accelerate equitable access.

5.1 Prevention Governance That Is Inclusive, Responsive, and Coordinated

Global HIV prevention governance is distributed across multiple institutions – UNAIDS, WHO, the Global Fund, PEPFAR, UNITAID, and others – with often competing mandates and timelines. Civil society is consulted but rarely empowered. National governments lack coordination mechanisms to align stakeholders or enforce accountability. Prevention is often deprioritized relative to treatment.

Reimagined Ecosystem: A prevention ecosystem governed by shared accountability, community co-ownership, and cross-sectoral alignment, backed by public health mandates and a systems-wide governance architecture.

Core Features:

- National HIV prevention compacts signed by governments, communities, and donors, with specific PrEP and prevention targets.

- Prevention coordinating councils embedded in Ministries of Health, including community, youth, and key population representatives with veto power.

- A multilateral coordination platform, aligned through a Global PrEP Task Force, that harmonizes guidance, funding streams, and technical support.

- Civil society accountability scorecards, updated annually and integrated into donor and government performance reviews.

- National and regional governance structures aligned with HIV epidemic control functions, including surveillance, equitable procurement, and real-time risk mitigation.

Effective prevention governance must balance authority with accountability. It must institutionalize the voice and leadership of those most affected and create mechanisms that reward ambition, not just compliance.

5.2 Financing That Is Predictable, Pooled, and Purpose-Driven

Prevention financing is highly fragmented, with siloed budgets for commodities, training, demand generation, and monitoring. PrEP commodities may be covered, but services and staff are not. Funding is volatile, short-term, and disproportionately reliant on external donors. MICs face a severe investment gap.

Reimagined Ecosystem: A financing system anchored in sustainability, flexibility, and equity, where prevention is a guaranteed health benefit – not a discretionary program – and financing serves both scale-up and system-building goals.

Core Features:

- Global PrEP Delivery Fund pooling international financing for PrEP scale-up and systems building.

- Domestic co-financing benchmarks, requiring countries to increase incrementally investment in prevention over five years.